Bristol Food Policy Council: Catalyst and enabler of the Bristol Food System

Isabelle Lacourt, 2015

Bristol has brought in Europe the North American culture of Food Policy Councils, a multi-stakeholder organization that thinks, assesses and acts to improve food systems at local level. Indeed, starting from Food Life Cycle, eleven food experts have been able to model a simple and consensual system based on circular economy, able to convince both city councillors and citizens to get involved. The city had already got a deep concern for environmental issues and was at the forefront of UK cities for its exemplarity for reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, green public procurement and waste management. It had also strongly bet on green economy development and innovation. This explains, amongst other things, the speed and scale of progress of the city to evolve towards the achievement of its Good Food project. In terms of funding, Bristol, City Council is pragmatic to recognize the difficulty to invest large amounts of money in food projects, in a moment in which public funding is getting lower, due to the crisis. Therefore Bristol FPC first job has been to make an overall picture that encompass all food-related activities already running and to network and frame all of them, in order to successively build on it. This has allowed to take into account the existing voluntary action that is essential to fuel the project and that must be channelled for greater efficiency. Indeed in Bristol, the communities and small businesses are the heart of the work in progress urban food system.

To download : fiche_bristol.pdf (140 KiB)

A former port city located in a rural area, open to trade, to innovation, environmentally friendly

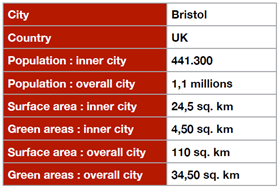

Bristol is located in South West England and is included into the Greater Bristol, a conurbation which contains and surrounds the city that corresponds to the former county of Avon. Bristol has been a city with a county status since medieval times. Nowadays, Bristol City Council (BCC) consists of 70 councillors representing 35 wards. On May 3th 2012, the city held a referendum, and citizens decided to vote directly to elect the City Mayor instead of having a leader chosen by the councillors.

United Kingdom’s eighth most populous city, Bristol is built around the River Avon and has also a short coastline. Indeed Bristol is a centre of culture, employment and education which prosperity has been linked with the sea since its earliest days. It is also a main university town. In the last 10 years Bristol City’s population has grown by 10% and the value of its economy has grown by 40%. The rate of unemployment is around 7%, very similar to national average rate. Banking and insurance, professional services, health and social care, education, creative industries, electronics and aerospace industries, leisure and tourism, are among the main activities of the city. Health and social care but also education, retail and distribution sectors are among those providing more jobs. In the last years, green economy, especially digital and low carbon industries sectors experienced an encouraging +4,7% growth rate.

It is currently estimated that 10% of jobs are related to food systems, from production to consumption. Indeed over 2.000 food catering business are registered in Bristol. Most of them are small companies including food takeaways, coffee shops, etc. A part of these food-related jobs also derives from public food service. Hospitals, Care homes, schools canteens represents 25% of catering business, whereas another 24% is related to workplaces’ canteens.

The South West region is the largest agricultural area of UK and also the country’s most rural region with more than half of its five million residents living outside towns and cities. Agriculture is employing 3% of the population and generating a share of gross added value above the national average. It is predominantly a grazing livestock area, mainly for milk production. Cereals are largely used for livestock feed. There is also a consistent production of vegetables (potatoes, carrots, parsnips, cauliflowers, etc.). 175.000 hectares are organically farmed, or in-conversion, which represents 9% of the total agricultural area, compared to the national average of 4%. 37% of the nation’s organic producers and/or processors, and 20% of the England area of land are located in the South West Region.

Recently, Bristol has been awarded by the European Commission as the 2015 European Green Capital, and is preparing to welcome a series of events related to this initiative. The jury recognized it as an efficient city with a growing green economy and « its potential to act as a role model for UK, Europe and the world ». Indeed the city aims to be a « Laboratory of Change, based on innovation, learning and leadership. »

Starting point and milestones of the project:

A local contribution to Global Climate Change

In 2000, Bristol was the UK pilot of the Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI)’s Cities for Climate Protection programme. The City developed the Bristol Climate Protection and Sustainable Energy Strategy that set a target to reduce emissions by 60% by 2050 from a 1990 baseline. It was one of the first UK municipalities to adopt such a strategy. In 2002 it adopted a plan to improve its environmental performance, followed in 2004, by a Climate protection and Sustainable Energy Strategy and Action Plan (CSESP). To implement this action plan BCC created a dedicated 4 persons staff team, in addition to specialists working on energy and biodiversity management. Since the 2004 strategy, Bristol successfully reduced its CO2 emissions by 15% between 2005 and 2009.

In 2009, Bristol joined the Covenant of Mayors and set more ambitious CO2 reduction targets to reduce emissions by 40% by 2020 and 80% by 2050, from a 2005 baseline. To meet these commitments it created the current strategy and action plan – The Climate Change and Energy Security Framework. Today, Bristol can claim to have the lowest CO2 emissions per capita of any major city in the UK. To reach such a result the city has invested 30 million pounds to reduce emissions from its own process (such as street lighting, non-domestic building savings, staff awareness, biomass boilers etc.).

From 2001 to 2011 it implemented 2 successful Transport Plans, focusing on managing demand, improving public transport and cycling, and encouraging ‘active travel’ to successfully reduce private car use, investing 100 million pounds to reduce CO2 emissions from transport. Indeed, this has produced a true cultural change among citizens, making them use less their cars not only for leisure but also to go to work. Since 2001 the city also invested up to 1 million pounds in the program « Bristol Green Doors », to support community action and run educational events to inspire, encourage and enable domestic green refurbishment.

From Bristol Local Plan (1997) to the Core Strategy (2010)

“ Bristol’s Sustainable City Strategy aims to reduce Health & Wealth Inequality, raise the aspiration and achievement of our children, young people and families, make Prosperity Sustainable, in a city of Strong and Safe Communities. Challenges are: Climate change, Regeneration and Affordable Housing, Transport and Digital Connectivity. Culture & Creativity are the best opportunity”

Within such a vision, the Parks and Green Space Strategy was adopted in 2008 in response to the high demand for good quality and accessible green space:

“green infrastructure can make the urban landscape more attractive whilst also providing opportunities for sports and recreation, active travel, wildlife, food growing, climate change adaptation such as urban cooling, flood storage capacity and pollution amelioration.”

The management of these green infrastructures is related with the Bristol Biodiversity Action Plan also adopted in 2008. Indeed city’s green infrastructure has been recognized to provide essential ecosystem services such as flood storage, carbon absorption and reducing the urban heat island effect. There is an on-going commitment to review existing wildlife sites to ensure that they remain worthy of protection. Since 2010, the area of protected sites has increased by 6.5 ha. In 2012, the city council and the Avon Wildlife Trust funded a 3-year 300.000 pounds project: « Feed Bristol » to promote wildlife friendly food growing at the Feed Bristol Centre a 7-acre site. 12.000 people of all ages and backgrounds including school children are encouraged to grow their own food on-site in an organic and wildlife friendly manner supported by experienced horticulturalist and a team of ‘Growing Leader’ volunteers. The Core Strategy also includes Strategic planning policies to ensure local, sustainable management of waste. Bristol has the lowest waste per capital of any major English city and substantially (23%) lower than the UK average. During the last full financial year 2011/12, 46.8% of municipal waste was recycled, reused or composted. Recyclable waste is bulked up at a local depot before being sent to various re-processors for recycling. The City Council requires the waste collection contractors to report the destination of all waste collected in Bristol and provides this information to citizens – to give them confidence that waste collected for recycling is recycled. All waste collected for recycling is processed in the UK.

From the Sustainable Procurement Strategy to the City Food Policy Council

The City Council has implemented a Sustainable Procurement Strategy in 2009, containing a set of eleven objectives to procure sustainably and influence others to do so. Under this strategy, and through a national programme for sustainable procurement, Bristol City Council has advised and run the UK South West Sustainable Procurement Network, through actions of training, organization of conferences and hosting a best practice website. By increasing the share of the total consumption of eco-labelled, organic and energy-efficient products, the City Council has substantially improved the environmental performance of its procurement, by setting up Public tenders that give weight to green issues such as packaging, sustainability of materials, design, global warming and ozone depleting potentials, suitability for intended use, environmental performance in use or product or service lifespan. Food procurement was included in such an approach.

In 2010 the City launched a municipal Food Charter that addressed all aspects of the food system and was intended to frame and give long term perspective to the food purchasing policy. The Food Policy Council was launched one year after, in 2011, at the March Bristol Food Conference and included 11 members, belonging to different organizations and bringing high level expertise from the following sectors such as food business (production, wholesale, catering, retail), local government, business development, Health, Community, Education/training NGOs specialized in food sustainability, including a local organization gathering experts and consultants: Bristol Food Network C.I.C. voted to « support, inform and connect individuals, community projects, organisations and businesses who share a vision to transform Bristol into a sustainable food city ».

In parallel and in synergy, Bristol was also one of five initial Partners in the EU URBACT II project ‘Sustainable Food in Urban Communities’. Indeed the project first concern was about the reduction of food system carbon impact and matched perfectly with the Bristol Climate Protection and Sustainable Energy Strategy. But the project also focused on the development of a local strategic group of food professionals and the production of an action plan: this aligns perfectly with new-born Bristol Food Policy Council and its agenda to foster sustainable food systems in the city.

The leverage: when communities and small businesses are the heart of the work in progress food system

Public Food Service: using the level of green procurement

According to the Sustainable Procurement Strategy that has been implemented since 2009, Bristol has reached good standards of food procurement with 30% of school meals being prepared with organic food. On the top of that, other quality and sustainability criteria have been used such as 45% of frozen fish is certified MSC (Marine Stewardship Council), 100% of banana come from fair trade market, 100% of eggs are free range which warrants a better quality than battery farmed eggs and more than 45% of food locally produced. Schools in Bristol have joined the UK national programme « Food for Life Partnership » to transform their food culture. This programme develops a holistic approach with a 3 level award system to encourage activities in all aspects of food systems. Following five years of full grant funding, the programme is now being commissioned by Local Authorities to address health and wellbeing priorities in their areas. If the city has played the green procurement card to increase food sustainability, the food project has really expanded with the launch of the City Food Policy Council.

The great adventure of Bristol Food Policy Council (Bristol FPC)

The founding publication « Who feeds Bristol? Towards a resilient food plan. » (Carey, 2011) drew a picture of food system, from cradle to grave that prepared the ground for thinking new food strategies for the city. In particular this research highlighted a model for Bristol food system based on community needs in terms of (1) Land use and food supply, (2) Food business and (3) Staple food. This research also mapped a series of actions in a plan designed to build circular economy based on a life-cycled food system, in which end-of-life (managing waste) is reconnected to food production, distribution, consumption. The main work areas are :

-

Support community food enterprise models

-

Transform Bristol’s food culture

-

Safeguard diversity of food retail

-

Safeguard land for food

-

Increase urban food production and distribution

-

Redistribute recycle and compost food waste

-

Protect key infrastructure for local food supply

-

Increase markets for local food producers.

In the beginning of its activity Bristol FPC has been able to summarize and simplify these work areas on a very synthetic and simple message on Good Food being »good for people, good for places and good for the planet », in order to raise awareness and consensus among all the population. Indeed Bristol FPC invites all citizens, either individuals or businesses to sign the « Bristol Good Food Charter« .

In 2013 all the work areas were re-elaborated into an action plan: « A Good Food plan for Bristol »: »The good food plan advocates a ‘food systems planning’ approach for Bristol in order to build a food culture for the city that has the health of people and planet at its heart.« (Source: Bristol FPC).

Many actions running in the city were already underway prior to the formation of the Bristol FPC and were brought forward for endorsement, taking place and making a renewed sense in an overall picture.

Indeed there are no specific budget lines to fund sustainable food projects and activities. National funding such as National Big Lottery’s Local Food Funds supported three projects in Bristol. Many of the projects are light and financially autonomous. Many local people are engaged in supporting sustainable food systems at different levels: as public sector staff, community groups or individuals. They are all enrolled by Bristol FPC, or the network of food professionals Bristol Food Network, or at the moment the task force Bristol Green Capital, created to manage all the events related to the award “2015 European Green Capital ».

Actions cover issues as diverse as:

-

community food growing with urban agriculture projects run by charities, community organisations, local groups and social enterprises on land owned by Bristol City Council

-

the redistribution of food destined to landfill and still edible by a local branch of a national charity specialized in redistributing surplus food

-

empowering people to make better use of food, in one of the poorest neighbourhood of Bristol. - campaigning to change the food culture.

-

etc.

Bristol FPC is also working with Public Health Bristol on two specific issues: the strong correlation between health and food (Maslen et al., 2013).

More recently it has got into urban food governance issues with a report based on interviews made to [Bristol City Council staff->bristolfoodpolicycouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/WHO-Food-and-Planning-Review-BCC-040614.pdf]. This report is a step forward and a useful contribution to highlight how city food policies can provide a platform for action that exemplify very straightforwardly to all citizens how the cities daily work for fundamental issues regarding their wellness and quality of life.

In particular it underlines how useful is a clear message, such as been the Good Food Charter, in order to effectively convince, not only citizens but also City Councillors, who have not been educated to understand the connections of food with the usual priorities of urban planners.

The role the Bristol City Council wants to give to itself is more to be a « catalyst » and « enabler » than a director. However City Councillors also recognize the importance to establish a leadership and to create internal mechanisms to coordinate all food related activities that can affect so many different sectors and functions in order to raise efficiency.

“The food system can be influenced but not controlled. The Council needs to act as a catalyst and enabler, creating an environment that supports small innovators (whether embedded in a community or independent entrepreneurs) in a wide variety of ways. The Council can strengthen its influence though a number of supportive actions including permissions, co-ordination, shaping projects and providing access to data, land or knowledge for third party projects.”

Sources

-

Joy Carey, (2011), Who feeds Bristol? Towards a resilient food plan. bristolfoodpolicycouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Who-Feeds-Bristolreport.pdf

-

Christina Maslen, Angela Raffle, Steve Marriott, Nick Smith, (2013), « Food poverty - What Does the Evidence Tell Us?", Food and planning developmental review, Bristol City Council. bristolfoodpolicycouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Food-Poverty-Report-July-2013-for-publication.pdf

-

Food and planning developmental review. A report based on interviews with Bristol City Council staff about their work on food, May 2014. bristolfoodpolicycouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/WHO-Food-and-Planning- Review-BCC-040614.pdf

To go further

-

EU Green Capital Award 2015 ec.europa.eu/environment/europeangreencapital/ - Core Strategy (2010) City plan: www.bristol.gov.uk/page/planning-and-building-regulations/planning-core-strategy

-

EU URBACT II project ‘Sustainable Food in Urban Communities’ urbact.eu/en/projects/low-carbon-urban-environments/sustainable-food-in-urban-communities/partner/?partnerid=646

-

Urban and Community Food Strategies. The Case of Bristol, International Planning Studies Volume 18, Issue 1, 2013 - bristolgoodfood.org - Helping create a good food system for Bristol: - « Bristol Good Food Charter » bristolgoodfood.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/The-Bristol-good-food-charter.pdf

-

« A Good Food plan for Bristol » bristolpound.org/blog/2013/12/05/bristol-food-policy-council-launches-good-food-plan-for-bristol/