FoodWorks: Innovative urban food programs in New York City

Isabelle Lacourt, 2015

NY city has been leader in engaging innovative and remarkable urban food programs for many years under the impulse of Mayor Bloomberg. Elected from 2002 to 2013, he gave a strong importance to food issues, starting from the problems related to obesity epidemic up to the construction on a vision that embraces the whole food system in a Life Cycle Thinking approach, turned into the implementation of the bases for a comprehensive Food Metrics system. Besides this work a whole range of local laws and communication campaigns have framed a cultural change that turn healthy food into an essential and transversal element in the life of all New Yorkers. Since 2007, the Mayor’s office of Food Policy was established and has coordinated NY Food Policies. Today the question of a NY Food Policy Council is raised by several experts. Indeed, Food policy councils are a subject of great interest in the USA, especially during recent years. There is a growing desire on the part of citizens to be part of the policy formation process. The Community Food Security Coalition conducted a survey that highlighted the increase of FPCs in North America, from 111 in 2010 to 193 in May 2012. Indeed, continuity should be given to this office independently from the mayor’s degree of sensitivity to food issues: moreover it should be enlarged to citizen and stakeholder inputs to generate more innovation and synergy.

À télécharger : fiche_nyc.pdf (200 Kio)

A densely populated city merged in a grain-growing region

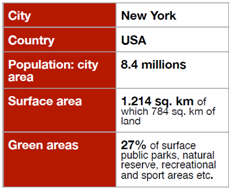

New York City (NYC) is the most-populous city in the United States, with an average population density of 10.000 inhabitants per km². Not only, it also welcomes 52 million tourists on an annual basis and half a million people commute into the city every day.

Throughout its history, the city has been a major port of entry for immigrants into the United States. Today, approximately 37% of the city’s population is foreign born. There is a very high ethnical diversity, although three communities, Afro-American, Jewish and Puerto Rican are dominant in the city. There is a high degree of income disparity among the population. NYC has the highest density of millionaires, whereas some boroughs of the city are very poor. As many other cities in the USA, it faces high levels of obesity among both adults and children. Over the years, economic pressures have tied obesity with hunger, both conditions that affect disproportionately poor populations. New York is well known to be a global hub of international business and commerce and one of three « command centers » for the world economy (along with London and Tokyo). Many major corporations are headquartered in New York City. High technology and biotechnology sectors are well developed, such as is the advertising industry. Other important sectors also include research, nonprofit institution and universities. The food-processing industry is the most stable major manufacturing sector in the city. Food making is a $5 billion industry that employs more than 19.000 residents. The city is embedded in a larger metropolitan area, one of the most populous urban agglomerations in the world, with more than 22 million inhabitants living in an area covering 34.490km².

NYC is part of the New York State (NYS) which has a rich agricultural heritage. Main productions are dairy farming, cereals (corn, soybean, wheat), field vegetables and potatoes, fruit trees. NYS statistics indicates a farm labour force of about 35.000 people, with an average age of the principal operator of 57. For 90 years, an independent association: the Regional Plan Association has been working to improve the New York metropolitan region’s economic health, environmental sustainability and quality of life through research, planning and advocacy. In particular it tackles land-use planning related topics such as Community design, economic development, energy, environment, housing, transportation, etc. NYS has a long tradition with food policies connecting agriculture and communities. In 1984, Governor Mario Cuomo launched the first New York State Food Policy Council, on Food and Nutrition policy. That Council included the leadership of seven state agencies, including Health, Education, Agriculture, Social Services departments. It also included a non-governmental advisory committee representing agriculture, nutrition, food production and consumer interests. In 1987, spurred by the Food Policy Council, the State adopted a Five Year Food and Nutrition Plan, linking an adequate food producing system in NYS with healthy food access to all the population.

The council ended after Governor’s term. A second council was created in 2007 (see www.nyscfp.org/). Recently, a « Report and Recommendations by the Workgroup on Food Procurement - Guidelines to the: New York State Council on Food Policy » was released (2012). In 2013, the NYS CFP also conducted a survey on local food policy councils and organizations in New York State that focus on anti-hunger, farm, nutrition and other food system related issues. The NYSCFP has also created a Local Food Policy Workgroup to make synergies between government and grassroots efforts. In parallel, it is also supporting local food supply chains, giving value to local agriculture production. Besides farmers’ markets reinforcement to improve fresh food access to the State population, it has launched touristic promotion projects. Few stores have been open in strategic spots such as airports, highways to sell local food productions such as wine, spirits, cider, beer, maple syrup, cheese under the brand « Taste NY ».

From the fight against hunger and obesity to a long term vision to improve NYC’s Food System

Since the 1970s, the dramatic increase of obesity rate in both adult and children population has been a main food challenge faced by the city. The population of obese and overweight people reached 53% in 2002, and 56% in 2012 despite 10 years of active commitment from NYS and NYC. Over this 10 year period, it became clear that obesity challenge is intertwined with hunger, both correlated with poverty. Indeed according to a survey conducted by the Food Bank, 32% of the population had difficulty affording basic food in 2012, against 25% in 2002. It must be said that this percentage increased up to 48% at the peak of recession during last economic crisis, highlighting how much food security is critical for citizens’ welfare.

Three initial priorities to contrast hunger and obesity

Improving Access to Food Support. Food Policies started to develop under Mayor Bloomberg administration in the early 2000s with the improvement of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called Food Stamps), a subsidy system for low income citizens. In 2002, 10% of the city’s population received SNAPs benefits. In 2013, up to 22,5% of NYC population is now concerned by this program. Since 2002 many improvements have been done, either by NYS and NYC to increase the number of SNAPs recipients, reducing bureaucracy procedures (online applications in 2004, longer SNAP re-certifications in 2008), easing access to information (call centers open in 2008). The city also made efforts to increase SNAPs participation by doing a large scale data match to identify potential recipients not receiving yet food benefits, followed by outreach to those identified.

Improving retail access to healthy food . The effort was not only made to improve food access in terms of quantity but also in terms of quality, by providing healthy food to lower-income populations.

In 2005, « Health Bucks » were introduced as pilot project in South Bronx area. These paper vouchers, worth $2 each, were developed and distributed by NYC Health Department District Public Health Offices to allow recipients to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables. As a long term farmers’ market incentive program, they were extended in 2006 to other areas (Brooklyn and Harlem). They have been linked to a pilot electronic payment model, today widely used (Baronberg et al., 2013), by which the New York State Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA) delivers cash and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits to New York State’s recipient population.

In 2006, the first Shops Health NYC, originally named Healthy Bodegas, were launched to contrast healthy food deserts in the city by increase nutritional offerings in at-risk neighborhoods. The project was implemented in different steps with the help of successive campaigns such as:

-

»Moooove to 1% Milk« . Participating bodegas agreed to carry more 1% fat milk, display posters promoting low-fat milk and distribute health information to customers. The campaign started with 15 bodegas and expanded to more than 1000.

-

»Move to Fresh Fruits and Vegetables« : the Health Department worked with 520 bodegas in Harlem, the South Bronx and North and Central Brooklyn to increase the availability, quality and variety of fresh fruits and vegetables.

-

»Star bodegas« . In 2008, the Health Department built on lessons from the 1% fat milk campaign and the fruits and vegetables campaign to launch the Star Bodegas program. The program works with select bodegas – star bodegas – to offer and promote a range of nutritious foods, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, low-fat milk, low-calorie drinks, whole grain bread, low-sodium canned vegetables and soup, and unsweetened canned fruit or fruit canned in its own juice. Star bodegas are also encouraged to offer healthy breakfasts and lunches including fresh fruit and water or low-fat milk, as well as healthier snacks, such as unsalted nuts and low-fat yogurt.

Still in 2008, the legislation for a new class mobile produce vendor permits was adopted : « Green Carts » offer fresh produce in NYC neighbourhoods with limited access to healthy foods in some specific areas in Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens and Staten Island. This measure reinforces the dispositive to open healthy food shops in areas with limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables (Fuchs et al., 2014). They are compatible with the municipal electronic payment system.

Increasing the nutrition content of food served by the city The city government has also worked over the nutritional quality of public food service. In 2008, it established standards in order to limit the use of salt and calories and to require minimum servings of fruit and vegetables in all meals served in schools, city government cafeterias, elder care and childcare facilities, city jails and prisons (over 2,5 million meals served daily). Such standards were extended to beverage vending machines in 2009 and to all food vending machine contracted by the city in 2011.

The City Health Code and Rules changed to require chain restaurant to post calorie information on menus. NYC intensified over the years its campaigns against obesity raising a great public attention; however it did not get a full consensus among the population and food companies. In 2012, organizations such as American Beverage Association, Teamsters, National Restaurant Association, etc. engaged a lawsuit to contrast the size reduction imposed by the NYC Board of Health on the containers of sugar-sweetened beverages. The city is now appealing against the decision of the judge who has ruled such plan invalid in first instance.

The Mayor’s Office of Food Policy (MOFP)

This office was established in 2006 and leaded by a Food Policy Coordinator, reporting to the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services and collaborating with advocates and service providers. It also convenes the Food Policy Task Force, comprised of representatives from across City agencies and the City Council. MOFP has been receiving funding from the City’s Center for Economic Opportunity (CEO): CEO develops and implements evidenced-based programs aimed at poverty reduction. CEO’s support of food access and economic opportunity programs includes the Health Department’s Shop Healthy initiative (formerly the Healthy Bodegas program) and the Food Handlers’ Certification Program (food safety issue).

It has also been working to create a broader food policy umbrella for existing and new programs, with the aim to oversee the City’s effort on improving the sustainability of its food system, reducing programmatic overlap, fostering interagency communication, engaging stakeholders, and strengthening public-private partnerships.

NYC has released its strategy for sustainability since 2007: PlaNYC (www.nyc.gov/planyc). In addition, the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability (OLTPS) was established since 2008 to coordinate with all City agencies to develop an efficient urban environmental strategy. Therefore several « PlaNYC Food-Related initiatives » have started to be mapped.

In parallel with the main MOFP’s achievements, the Office of the City Council Speaker, at that time Chris Quinn, produced a report « Food Works : A vision to improve NYC’s Food System”, first published in 2010 and updated in 2013.

“This FoodWorks plan explores some of the ways in which the many pieces of our complex food system are interconnected, sets goals to help us make better choices, and presents a blueprint for some initial steps, both large and small, that can make the system stronger and more sustainable for generations to come.”

The first report gives an update of all NYC food projects already running and an overall picture of food insecurity causes. As a roadmap, it lists all opportunities raised by a more sustainable food system based on 1- the availability of healthy affordable food for all citizens; 2- the support to local economy through the development of a regional food supply chain that contributes to mitigate environmental impacts. It follows a methodology of action that considers five pillars of food systems within a Life Cycle Thinking approach: agricultural production, processing, distribution, consumption and post consumption. For each of those it outlines long term goals, related strategies to reach such objectives and specific actions.

Although it does not constitute a binding policy, it has been an important milestone because health concerns, initially at the origin of actions to improve food consumption in NYC, have been starting to be articulated and integrated with environmental concerns.

The second report presents all achievements, recommends further strategies for all 5 pillars and introduces a food metrics system formalized in 2011 by the Food Metrics Act. Indeed, 19 indicators were identified by October 2012, and the conclusion of the second report of Food Worksis asking for the improvement of such metrics system as a process to develop further the NYC’s Food System.

Food metrics: to assess leverage actions’ efficiency

Reporting on NYC anti-obesity efforts

To end hunger with a food distribution system based on charity is a cost for the whole society. To end it with healthy food costs even more. Same is to create a culture of change. Benefits of such strategies can only be seen in a long term period. Obesity is ever a trickier challenge. Indeed some people argue that food choice is a personal matter.

Its strong efforts to contrast obesity, in particular among children, place NYC among the few cities reporting childhood obesity decline within the last years. Between school years 2006/2007 and 2009/2010 obesity rate was reduced from 21,5% to 20,5%, leading to an obesity decline of 5,5%1. Making healthy food available in schools and communities were the two main leverages. To give an idea about the work achieved, and the necessary investment, these are some of the actions described in the Interim Progress Report on the New York Obesity Task Force2:

-

125 $2500 grants awarded in 2012-2013 to develop wellness councils and activities in schools

-

789 water jets in schools to reduce soda consumption

-

350 school garden grants

-

1379 salad bars in school restaurants

-

3482 teachers of elementary schools trained to do proper physical activities courses

-

300.000 visitors to the free physical activity programs in City parks

-

sake walking corridors close to schools.

These actions are summed to those addressed to the whole population to encourage healthy eating, and to promote physical activity. However despite all these efforts, over the period 2002 – 2012 obesity among adult population increased from 18 to 24%. These figures show how expensive it is, on a long term basis to get only the hope to reverse the trend.

But the increasing awareness about the « hidden » costs either on environment or on health of such global food system has been a strong leverage to induce more and more decision makers to change overall vision on food and implement more sustainable food systems during last decades.

For instance, the Bloomberg administration was very active to frame this issue by switching it from an individual concern to a collective one, highlighting in particular obesity fallouts over all city taxpayers, reaching 4 billion dollars, to cover part of health expenses.

The role of public plate

It is impossible today to measure those hidden costs with the same immediacy and accuracy than it is for the cash flows. Still a strong effort needs to be done to develop suitable metrics to report as accurately as possible on the effort to improve food systems. To create a Metrics system is one of the major challenges that are faced today by those who want to justify public investment in sustainability. NYC Food metrics system is based on 6 issue areas among which City Food Purchasing and Food Service.

NYC highlights the role of public plate as a lever3, not only to improve health but also to support local and regional agriculture and food producers and to create stable jobs. For instance the department of education, whose annual budget is over 420 million dollars, is the second institutional purchaser in the USA, just after the US department of Defense. NYC serves approximately 260 million meals and snacks per year, in schools, senior centers, homeless shelters, child care centers, after schools programs, correctional facilities and public hospitals. In five years, from 2008 to 2013, due to a very strong effort from all municipal agencies concerned, 89% of these meals have been complying with the Nutrition Standards established by the city, aiming a reduced use of sugar and fat and an increase of fruit and vegetables. In addition to promoting healthy eating patterns, a set of guidelines have been added in 2012 to the public procurement law LL50 of 2011 to increase seasonal and local food provision.

Financial constraints limit the City’s ability to achieve food security and healthy food objectives. As the number of meals being served is enormous, even a single penny per serving in additional cost can be prohibitive. Amounts over $100.000 may involve Competitive Sealed Bids. City agencies are required to take the lowest bid from a reliable and responsive bidder. Smaller agencies that contract with the City may purchase directly from wholesale or even retail vendors. As soon

as spring 2013, local preference was acknowledged in food bids solicitations.

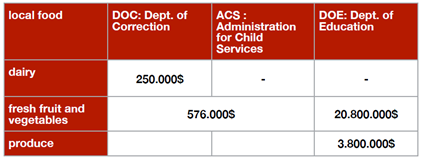

Table 1 highlights the budget of public food service to purchase local food. In 2013, the overall budget of agencies Dept. of Correction (DOC) + Administration for Child Services (ACS) + Dept. of Education (DOE) reached the amount of 25.000.000$. Only DOE has spent 0,14$ to buy local/seasonal food, for each of the 172.000.000 meals and snack served.

These figures highlight the economic leverage of public procurement. By comparison, the Health Bucks program which gives a free 2$ coupon to buy healthy food in 2011, led to an amount of sales of fresh food in farmers’ market of 973.621$. Indeed instead of 2$ given in pure gratuity, as in the case of Health bucks the public agencies shift a part of their budget to a specific range of suppliers. It is clear of course that although these different systems reach specific and synergic objectives and are all necessary for different reasons, however, in the case of public procurement, the economic strength of large buyers can be used to build up sustainable local food systems.

“Increasing enrollment in the NYC School Lunch Program by 15% would create 883 new union jobs.” (The Public Plate in NYC. A guide to Institutional meals) , thus adding to the City’s tax base. Sourcing from nearby farms also keeps the money in the region, and helps farms remain in business. Participation in federally funded meal programs draws in federal dollars to circulate in the NYC economy.

However, the conflict between budget constraints and stimulation of the local economy arises every time a distant supplier offers a cheaper price than a nearby source. Institutional meals participate to the consolidation of wholesale distribution services initially designed to deliver local fresh food to grocery stores, bodegas, restaurants, caterers etc. According to Greenmarket Co:

“In the beginning, the team anticipated that restaurants and specialty retailers would drive sales, but increasingly much of their business is derived from sales to institutions (this year institutional sales are expected to surpass orders to restaurants). This shift can be attributed to the outreach Greenmarket Co. engages in over the winter months to promote the program, the high volume of food required by institutions, in addition to the consistency of their ordering. Public and private institutional clients include eight DFTA-funded senior centers, soup kitchens, food pantries and other nutrition assistance programs. In all, since launching the program in 2012, Greenmarket Co. has distributed more than 115,000 pounds of food to 19 institutions – purchases that account for more than $70,000 in income for regional farmers” (Source The Public Plate in NYC. A guide to Institutional meals).

Besides food procurement other investments are necessary to allow that public plates are filled with healthy and good food. Among the main projects:

-

Food delivery is another strong challenge to improve the service. Most NYC schools have only enough storage space for a few days food; they require delivery 2-4 times a week for basic items, and daily for bread and milk. While the DOE is able to negotiate very low prices for the food items it buys in large quantity, much of the saving is eaten up by “conveyance charges”, charges that vendors add to compensate for the time or effort needed to deliver food to the site. Therefore to increase food storage would allow to optimize food delivery and by consequence to reduce environmental impacts related transport.

-

The city is also investing to improve kitchen equipment to facilitate the compliance of Institutional meals with Food Standards. For instance salad bars have become a popular strategy for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in schools, but they require very specific equipment in order to meet health and food safety regulations. Since 2004, the City has installed more than 1.300 salad bars in its schools; it is on track to offer a salad bar in every school by 2015.

-

About the question of food waste, the use of standardized recipes and many pre-cut products reduces on-site waste. Plate waste is not returned to the kitchens, but food service administrators watch which items are not being consumed to the degree they should be and make menu suggestions in light of these observations. A recent 30% reduction of the amount of hot cereal available is an example of such a change.

Declining childhood obesity rates – where are we seeing the most progress?, (2012), “Health Policy Snapshot Childhood Obesity”, Issue Brief; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [a(http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2012/rwjf401163) www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2012/rwjf401163

2 Reversing the Epidemic: The New York City Obesity Task Force Plan to Prevent and Control Obesity, May 31, 2012. www.nyc.gov/html/om/pdf/2012/otf_report.pdf

3 The Public Plate Report in New York City. A Guide to Institutional Meals. New York City Food Policy Center at Hunter College, 2014. nycfoodpolicy.org/publications/research/

Références

-

With the acknowledgement of Kim Kessler, Policy and Special Programs Director, Resnick.

-

Sabrina Baronberg, Lillian Dunn, Cathy Nonas, Rachel Dannefer, Rachel Sacks, (2013), The Impact of New York City’s Health Bucks Program on Electronic Benefit Transfer Spending at Farmers Markets, 2006–2009, “Preventing Chronic Diseases”, 2013; 10:130113. dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.130113

External Web Site Icon

-

Ester Fuchs, Sarah M. Holloway, Kimberley Bayer, Alexandra Feathers, (2014), Innovative Partnership for Public Health: An Evaluation of the New York City Green Cart Initiative to Expand Access to Healthy Produce in Low-Income Neighborhoods, p. 9, Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs Case Study Series in Global Public Policy: 2014, Volume 2, Case 2. Columbia SIPA School of International and Public Affair. sipa.columbia.edu/system/files/GreenCarts_Final_June16.pdf

-

Declining childhood obesity rates – where are we seeing the most progress?, (2012), “Health Policy Snapshot Childhood Obesity”, Issue Brief; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2012/rwjf401163.

-

Reversing the Epidemic: The New York City Obesity Task Force Plan to Prevent and Control Obesity, May 31, 2012. www.nyc.gov/html/om/pdf/2012/otf_report.pdf

-

The Public Plate Report in New York City. A Guide to Institutional Meals. New York City Food Policy Center at Hunter College, 2014. nycfoodpolicy.org/publications/research/

En savoir plus

-

New York City Food Policy Center’s website : nycfoodpolicy.org/ NYC Food Policy: 2013 Food Metrics report www.nyc.gov/html/nycfood/downloads/pdf/ll52-food-metrics-report-2013.pdf NYC Food Policy: 2014

-

Food Metrics report Available on www.nyc.gov/html/nycfood/downloads/pdf/2014-food-metrics-report.pdf FoodWorks.

-

A vision to improve NYC’s Food System. council.nyc.gov/downloads/pdf/foodworks_fullreport_11_22_10.pdf