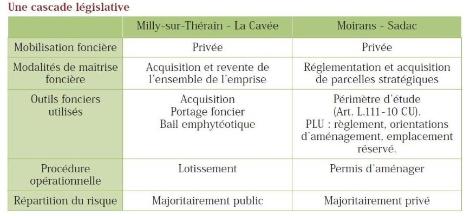

Two examples of municipal land policies

Persyn Nicolas, mars 2015

La Revue Foncière / Association Fonciers en débat

A look at two types of ordinary municipal land policies, combining intervention on land and regulatory tools, on the outskirts of medium-sized urban areas.

A recurrent discourse attributes the housing crisis to the lack of local land policies in favour of housing. This would explain the lack of production possibilities, particularly in the already built-up urban fabric. The main targets of this criticism are well known: the municipalities, too small, too numerous, without means; the mayors, in turn too Malthusian or too lax; always too inclined to defend municipal interests rather than the interests of the conurbations. But this discourse, often relevant, sometimes lacks consistency: it neglects to take a precise look at what happens on a daily basis in our municipalities in order to understand how municipal land policies are carried out for housing production. This is what this article sets out to do, by developing two case studies, resulting from the work of a thesis1. They correspond to two operations, in two municipalities with different profiles and contexts. In each case, the objective was to understand which land policy had been implemented, using which tools and with which results. The focus here is on ordinary territories, outside the exceptional operations often highlighted in academic and professional literature. These two examples show that communal land policies do exist, and that they can be relatively effective if they are adapted to the context in which they are implemented, although they remain operational support policies2.

In Milly-sur-Thérain, the logic of land portage

The first case study concerns the La Cavée operation in Milly-sur-Thérain (Oise). This is a peri-urban commune of 1,650 inhabitants, about ten kilometres north of Beauvais, which has been developing at a moderate rate for about thirty years (+0.9% inhabitants per year between 1982 and 2012) by successive additions of housing estates of about forty single-family houses in extension, a development trajectory in which the operation studied here fits. The operation emerged in 2007, when a private operator, Foncinord, whose main activity is the production of building lots in subdivisions, informed the commune of its desire to develop about sixty housing units on a 5.6 hectare plot of land in the urban extension. The operator has already negotiated with the owner and signed a promise of sale.

The project seems to correspond to the town hall’s desire to see the construction of new individual houses, and one might have thought that it would be content to let the operation take place in compliance with the PLU. However, out of a concern for control, particularly in order to integrate social housing into the operation, the municipality nevertheless wished to appropriate the land. It also owns an adjoining plot of land of about one hectare that it wishes to integrate into the project in order to open it up to the main road of the commune. However, the municipality does not have the means to acquire the private land directly, estimated at 15 euros per square metre by the estate agents, i.e. 840,000 euros. Negotiations between the owner and the operator led to a slight increase in this price, which was set at approximately 890,000 euros in the promise to sell, i.e. 39% more than the average annual budget devoted to investment between 2006 and 2012. In 2009, the municipality then turned to the Établissement public foncier local de l’Oise (EPFLO) to carry the whole of the operation’s right of way. The aim was not to exclude the private operator, but to guarantee control of the programme and the form of the operation through public ownership of the land for an intermediate period. After negotiations between the municipality, the EPFLO and the private operator, a programme and an operation set-up were decided upon. The programme includes 40 PLUS and PLAI social housing units (required by the municipality and the EPFLO), and 63 building lots, and comprises three phases, with approximately 20 social housing units in the first two. The operator Foncinord has already established contacts with a local lessor, the SA HLM du Beauvaisis, within the framework of another operation in a nearby commune. This landlord was quickly integrated into the operation.

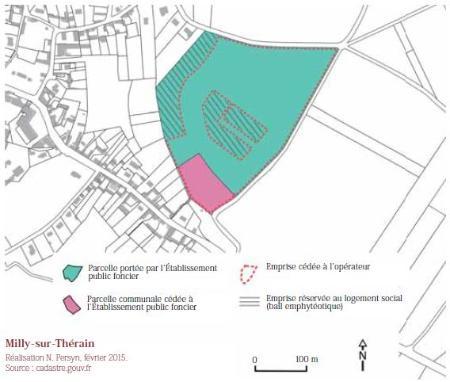

Milly-sur-Thérain, a land portage operation

The arrangement provides for the EPFLO to acquire the private parcel as well as the municipal parcel. Once the project has been truly decided, and in particular the permit has been granted, the majority of the right-of-way will be sold in three tranches to the private operator who will carry out the developments within the framework of a subdivision procedure. It is planned that the part of the land reserved for social housing will be kept by the EPFLO, which will make it available to the lessor via an emphyteutic lease. The main tool used here by the local authority is therefore the acquisition of land through the intermediary of land portage. Public intervention has made it possible to integrate social housing into a programme that was previously only available. The perimeter of the operation, induced by the mobilisation of private initiative, is made a little more coherent by the addition of a municipal parcel and the redrawing of the land by EPFLO within the framework of the portage. However, the logic of public acquisition and land portage chosen here transforms an operation that was originally entirely private into an operation where the risk is mainly public. For the operator, this is an advantage since he does not have to invest directly in the land, but can take the time to market the lots to secure his investment. Moreover, as the public intervention took place after the negotiation between the owner and the operator, it could not concern the control of the level of the land charge: the acquisition was made at the price fixed in the promise of sale, the municipality not wishing to take the risk of a withdrawal by the owner and not wishing to use a pre-emption or expropriation procedure. The long lease proposed by the Établissement public foncier allows the landlord to cancel the land charge, or rather to defer it over time (60 years). It is therefore at the cost of taking a public risk that the municipality has obtained control of this operation, while being unable to control the level of the land charge. The land portage agreement was signed in 2011, and the operator began marketing the lots. But the market was not buoyant, and the marketing was not a success. In June 2012, of the 33 building lots in the first phase, only 5 were reserved. After some time, the operator agreed to lower the price of the lots: while the original selling price of the lots was around 71,000 euros, i.e. approximately 115 euros/sqm of land and 290 euros/sqm of net floor area, in February 2014, the operator’s website indicated an average price of 65,000 euros, i.e. 100 euros/sqm and 260 euros/sqm respectively 3. This situation is rather problematic for the municipality, since although the land is held by the EPFLO, it has undertaken to buy it back no later than ten years after the signing of the agreement. However, the deadline is far from being served and the situation is not dramatic for the moment, as the time remaining to market the building lots is probably sufficient. The real problem is that the construction of social housing, which is ready to start, depends on the developments that Foncinord must carry out, but which it cannot undertake until it has marketed a certain number of lots. When we completed our investigations on the ground at the end of 2013, the operation had still not started, as the marketing of the lots was not progressing. Public intervention in the land market therefore made it possible to control the process, but did not guarantee that the operation would be completed.

In Moirans, strategic acquisitions and regulatory tools

The Sadac operation, the second case, is located on a former industrial site in the heart of Moirans, a large town of 7,800 inhabitants in the Isère valley, 20 kilometres north of Grenoble. As in Milly-sur-Thérain, the initiative of the operation is private: in 2005, the owner of the 3.2 hectare right-of-way puts his land up for sale, and two developers (Bouygues Immobilier and Cogeco, a developer from Isère) join forces to sign a promise of sale in order to develop housing. Unlike the previous case, the municipality does not wish to become the owner of the site. However, it does not give up control over the programme and the development of the operation, which it will do by using a series of land and regulatory tools.

Moirans, acquisitions and regulatory tools

The municipality has been the owner for several years of plots of land adjacent to the site. They represent an area of approximately 4,500 m². These acquisitions were made as sales were made, as the municipality wished to reduce dilapidated housing, while positioning itself in a sector that it knew was subject to change. Quickly after the start of the private project on the Sadac right-of-way, the municipality decided to integrate the plots it owned into the operation. The first municipal decision in this direction was the establishment of a study perimeter under Article L.111-10 of the town planning code (October 2005), which allows it to postpone a decision « on requests for authorisation concerning works, constructions or installations likely to compromise or make more expensive the realisation of a development operation which has been taken into consideration by the town council ».4 It is not a question of the municipality exercising this right to postpone a decision at all costs, but rather of determining the perimeter of the operation in a first official act, which then encompasses the plots of land owned by it. This is also a way of giving oneself time to develop a project in agreement with the operators. At the same time, Moirans was revising its land use plan into a local urban plan (PLU). It took advantage of the coincidence with the sale of the Sadac land to include development and programming guidelines for this sector in the PLU. The building or development permits submitted must be compatible with these guidelines, which cover communal land: the operators are thus obliged to come to an agreement with the commune for the implementation of the operation. Among the tools of the PLU, the commune also uses the reserved site. In December 2006, it purchased a 580 m² plot of land adjacent to the Sadac factory to the south-west by mutual agreement. It is using this opportunity to define a reserved site of 4,900 m² for a school, which straddles this new municipal property and the Sadac land. This provision implies that no construction other than a school can be built on this site5. The two owners, in this case the commune, and the developer (who is not yet the owner but who can file a permit under a sales agreement), must come to an agreement, unless the future owner renounces his rights to build on this site, which is unlikely. In 2007, after discussions between the municipality and the operators, a programme was decided upon, which included 24,000 m² net floor area of housing, including 12% social housing (which corresponds to the municipality’s expectations), 300 m² of commercial or tertiary surface area, road improvements and public spaces, as well as a new school group, on the reserved site. Through the joint use of the regulatory tools of the PLU and land tools (acquisitions, pre-emption), the municipality was therefore able to partially control the operation in terms of form and programme. However, while the operation seemed to be on track, the promoters withdrew from the project in 2007: additional studies revealed the pollution of the site, due to the former industrial activity, which implied additional clean-up costs that were not compatible with the land cost established in the promise of sale. The operation then remained at a standstill for several years. It can be seen here that the decision of the municipality to work essentially on the basis of its PLU and strategic acquisitions, while guaranteeing a certain control of the form and programme, does not however make it possible to relaunch the operation, which remains dependent on private initiative. As is often the case (Renard, 2015), it is a biographical event that unblocks the situation: the owner dies and his heirs wish to sell the property quickly, and are therefore willing to negotiate on the basis of a much lower price. A new developer, Trignat Résidences, then took a position and signed a new promise to sell, for 2 million euros, as opposed to 7 million for the price previously set (i.e. 62.5 euros/m² as opposed to 218.7 euros/m²). The project was then partly redesigned, while still taking into account the development guidelines. The programme became more precise and consisted of 290 housing units (22,000 m² of net floor area), including 12% social housing, 10,000 m² of green space, and 750 m² of shops. The project is divided into five distinct phases. Part of the development is to be carried out by the developer, another part by the municipality itself. When the final project was presented, the school was no longer part of the programme. This is because the town council has made progress on this point since 2007. Originally, the municipality wanted to create a new school complex. The decision to create a reserved area on this site was primarily a means of controlling the project and a guarantee that the facility could be built there if the municipality so decided. However, the elected representatives wanted to consider other possibilities for the location of the school in the municipality, and finally decided that the school would be located elsewhere. Originally, the size of the reserved area on the Sadac site corresponded to the area owned by the municipality to the north of the site. The idea was then to proceed with a land swap with the operator: the municipality would recover the area of the school complex and give up the equivalent in the northern part of the site. With the abandonment of the school complex on the site, the municipality has 5,500 m² of land with no immediate destination. For a time, it planned to build a retirement home on the site, but once again, it was decided to locate the facility elsewhere in the municipality. In the end, the land exchange was carried out, with the municipality recovering a right of way to the south-east of the site, but without this right of way there is still no precise destination. Between 2010 and 2013 the project was finalised, demolitions began, and a first development permit was filed jointly by the operator and the municipality, followed by the first building permits. At the end of 2013, the operation seemed to be well on the way to being completed. In this case, the various tools of the PLU and a strategic land positioning allowed the operation to be controlled, while maintaining a predominantly private risk-taking.

Clarifying the objectives of land policies

The two examples presented show, firstly, that local land policies exist in France, even in small municipalities. The two municipalities presented above are able to implement a variety of tools, and to combine them, to support land mobilisation and control what happens on these lands, with varying degrees of success. These policies, which are based on real political choices (the place of acquisition, regulatory tools, and private initiative in particular), correspond to coherent action programmes, drawn up up in advance, which sometimes resemble real strategies, as the case of Moirans shows. Secondly, these land policies are diversified. Far from a model inherited from the post-war period and from foreign experiences (especially from Northern Europe), which perhaps still marks too much the minds, communal land policies are not limited to a triptych of acquisition - development - sale of land charge, as the two case studies clearly show. In one case, public land acquisition, the possession of the tenements by the municipality (via the EPF) is the central tool for controlling the development process. In the other case, acquisitions do not have the same place: it is the PLU which is central, the possession of land in the operation being above all a way for the commune to impose a dialogue with the operator. Control is therefore not only achieved through possession, but can be based on other tools, regulatory, operational, etc. Land policies are not simply a matter of systematic acquisitions, but correspond more broadly to a public action programme that makes it possible to encourage, supervise and control the mobilisation of plots of land, their precise allocation (programme, form) and the conditions of this allocation (temporality, price). Secondly, we note that municipal land policies are operational support policies. The aim is to remove the land barrier to the emergence of housing operations, by controlling the effective allocation of plots. These land policies are thought out and deployed on the scale of operations, and not on a wider scale, communal or sub-communal. Although the preparation of the PLU could be a time for defining the municipal land policy, particularly in the planning and sustainable development programme, the land issue is only very rarely really addressed. Although the PLU are indeed land policy tools, they do not contribute to defining these policies at the municipal level. There is no logic for regulating the rate of mobilisation and even less for regulating prices. Although they were able to control the programme and the form of the operations, the two municipalities studied were not able - and in fact did not really try - to control land prices and the level of land charges. It can also be seen that they have not been able to prevent the processes from being slow: the Milly-sur-Thérain operation, initiated in 2007, has not yet been completed, while the Moirans operation has already been spread over more than ten years. Thus, municipal land policies are not regulatory policies. However, the marketing difficulties in Milly-sur-Thérain highlight the need to also think in terms of production and market rhythms. It is therefore necessary to distinguish between operational support land policies, which are necessary and exist, even in small municipalities with few resources, and regulatory land policies, which are lacking at the municipal level. The question is not so much whether or not there are local land policies, but rather what kind of policies and objectives are assigned to them. This calls into question the ‘solution’ regularly put forward in terms of land policies, namely the development and implementation of inter-municipal land policies. For operational support land policies, what is really expected from this change, since the tools and scales will be the same? For regulation policies, can a simple change of scale really change the situation? Are we not faced here with a double challenge, that of know-how, and that of a necessary political clarification, perhaps national, of the objectives of land policies, particularly in terms of price regulation?

-

1 N. Persyn, 2014. Mobiliser et maîtriser le foncier pour le logement : outils et pratiques en agglomérations moyennes, doctoral thesis in Urbanism and Geography, Université Paris I - Panthéon-Sorbonne, 485 p.

-

2 The case studies presented here focus on municipal land policies on the outskirts of two medium-sized French conurbations, the Voironnais and the Beauvaisis. Twelve municipalities and two EPCIs were studied using an empirical approach, based on interviews with local actors and the collection of information from municipal council minutes and other local documents. The analysis presents two types of local land policies as well as their limitations and the difficulties they face.

-

3 www.foncinord.com, accessed on 10 February 2014.

-

4 Article L.111-10 of the urban planning code (this is the urban planning code in force at the date of the deliberation).

-

5 Article L.123-1-8° of the urban planning code (this is the urban planning code in force at the date of the deliberation).