Putting everyday car sharing on the agenda

A framework by default, within a competitive ecosystem still under construction

Nolwen Biard, septembre 2023

Car sharing is not a new practice, having existed since the early days of the motor car. During the 20th century, collective use of the car was stimulated by periods of war and energy crises in Europe (Vincent, 2008) and the United States (Chan & Shaheen, 2012). Moreover, with the emergence of a student population in the post-war baby boom society and the promotion of hitchhiking by certain cultural movements, this form of travel was « almost elevated to the status of a way of life »: the 1970s proved to be « the golden age of hitchhiking » (Viard, 1999 in Vincent, 2008). However, collective use of the car has steadily declined and hitchhiking, i.e. being alone in a car, has become more widespread, particularly for home-to-work journeys. Despite its declining popularity, car-sharing has gradually been taken up by public and private players, and seen as a resource for tackling various public problems. However, this move up the agenda has been made in relation to public transport, by determining a potential by default, for journeys where public transport is not deemed relevant.

À télécharger : 2023.09.11_vf_etude_covoiturage.pdf (5 Mio)

The democratisation of the private car: towards car dependency and the reign of selfishness

Car dependency in a context of intensification and fragmentation of mobility

Between 1972 and 2019, the purchasing power of car mobility increased fourfold (Crozet, 2020). This reduction in the cost of owning and using a car has largely contributed to the spread of the car and its democratisation. It has opened up new opportunities for urban sprawl and for people to move further away from where they live and work. « The car is building a different kind of city, with extended boundaries, reduced densities, fragmented centralities and redefined distinctions », a city also described by Gabriel Dupuy as « the territories of the car » (Michel, 1997).

The deployment of the car thus accompanies the phenomenon of metropolisation, which, beyond being « a simple phenomenon of demographic growth in large conurbations, is combined with urban sprawl, the fragmentation of functional spaces and the recomposition of living environments » (Hamel, 2010). The car enables and accompanies the dispersal of traffic flows, leading to more diffuse urbanisation and density. These more fragmented mobility practices are increasingly difficult to cover by public transport. « New geographical structures of life based on travel between residence and workplace, but also many other sites (consumption, leisure, social life, training, etc.) are taking shape. It’s hardly surprising that each inhabitant is building his or her own living space within this mosaic, with its own specific places, social relationships and journeys ». (Di Méo, 2010).

As a result, the car’s ability to « do almost everything, almost everywhere » (Cerema, 2022) is becoming an essential attribute for access to a number of activities and opportunities. This is what Gabriel Dupuy calls « car dependency ». Regional planning is designed around the car, effectively excluding people who do not have a car. Having a driving licence has become a prerequisite for a large number of jobs, even though they do not necessarily require motorised business travel. In a business park on the outskirts of Paris, for example, a technician from the Plaine de l’Ain Community of Municipalities recounts how, following a mobility survey, she found that work schedules in companies were all different and shifted by 5 minutes to avoid creating a traffic jam at the exit. The flexibility and individualisation of mobility practices thanks to the car are making it more difficult to put in place public transport solutions.

The car is thus becoming indispensable for our journeys, but more generally for our lifestyles and our way of living in the region. 84% of households own at least one car, and 36% even own several (URF, 2019, in Bigo, 2020).

Multi-motorisation and the decline of car-sharing

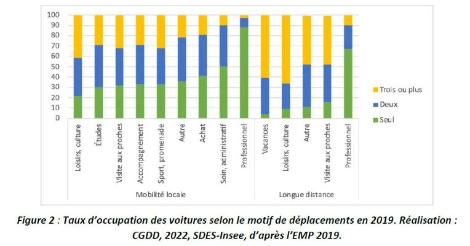

The intensification and fragmentation of travel practices, as well as the widespread motorisation - or even multiple motorisation - of households, have had the corollary of reducing the need to share a car. Between 1960 and 2017, the average occupancy rate fell from 2.3 to 1.58. It will reach 1.43 for local journeys in 2019. At the same time, the average number of cars per household rose from 0.97 in 1982 to 1.23 in 2019. Today, more than half of all car journeys of less than 50 km are made by a single person (CGDD, 2022). Self-sufficiency is particularly high when travelling to work: nine out of ten car journeys (88%) are made for work-related reasons (CGDD, 2022). This finding is echoed in the results of the Vinci Self-driving Barometer 1, which shows no improvement between the first edition (end 2021) and the most recent (early 2023), with the average rate of self-driving at peak times rising from 82.6% to 84.7%.

Conversely, daily journeys for leisure, study or to visit relatives are those that most often include at least one passenger.

Is there a passenger in the car? 15 The decline in collective and shared use of cars is also linked to the values conveyed by the car industry. This industry, supported by a powerful economy, spent 4.3 billion euros on advertising and communication in 2019 2, in France alone. This helps to make the car an object of consumption, desire and social distinction. The values associated with the car can be summed up in a few words: « freedom, individualism, mobility, speed, power and intimacy » (Paterson, 2010); words that are in direct contradiction with the practice of car sharing.

The challenge of « reversing the trend » in the face of car use that is having a serious impact on the climate, the environment and health

Today, the transport sector is the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases in France, accounting for 30.8% of emissions in 2019. The car is responsible for 96% of GHG emissions for local mobility and 56% for long-distance mobility 3. The impact of the car on the environment and our health is far from limited to greenhouse gas emissions: it consumes non-renewable resources, causes air pollution, emits fine particles, consumes space and artificialises land, damages biodiversity, etc.

Between 1960 and 2017, the transport sector saw a sharp rise in CO2 emissions, due to an increase in demand for mobility caused by population growth and an increase in the number of kilometres travelled per person. The fall in the average occupancy rate would be responsible for a 28% increase in CO2 emissions over the period (Bigo, 2020). Between 2008 and 2019, i.e. the last two INSEE mobility surveys, the stagnation in car occupancy rates led to a 7.5% increase in local car traffic, as a result of population growth and longer distances travelled (Bilan annuel des transports 2021, SDES 2022). The National Low Carbon Strategy (Stratégie Nationale Bas Carbone, SNBC) sets out France’s decarbonisation targets, with the aim of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. For the transport sector, five levers are detailed: moderation of transport demand, modal shift, optimisation of vehicle occupancy, energy efficiency of vehicles, and the carbon intensity of energy. The SNBC is therefore betting on a reversal of the historical trend of falling occupancy rates, « in order to act to reduce emissions » (Bigo, 2020). In the SNBC’s « with additional measures » (AMS) scenario, the occupancy rate of light vehicles for short-distance journeys would rise from 1.45 in 2015 to 1.75 in 2050. The average occupancy rate (including long-distance journeys) would rise from 1.6 in 2015 to 1.9 in 2050. According to the ambitions of the SNBC, this lever should make it possible to reduce GHG emissions from the transport sector by 11% (Bigo, 2020).

Car-sharing, a mobility solution defined by default, but invested with multiple objectives, without questioning its relevance.

Towards a diversification of the objectives associated with the development of car sharing

Teddy Delaunay, in his thesis on car-sharing in the Île-de-France region published in 2018, identifies three car-sharing regimes. The first, that of the scarce car, corresponds to a period when the car remains a scarce commodity: a certain number of people remain excluded from car mobility. They can gain access through hitchhiking or carpooling. Under this system, car-sharing is an informal practice, often associated with a militant lifestyle or serving the general interest (Vincent, 2008) and located « outside the concerns of the public authorities » (Delaunay, 2018).

The car in excess corresponds to the second regime of car-sharing: in this period, the spread of the car has become so widespread that it has become the source of an increasing number of nuisances. The most visible of these were air pollution, noise, congestion and accidents, all of which were denounced as public problems. Against this backdrop of excessive car use, car-sharing is gradually being adopted by the public authorities as a way of reducing the negative externalities of the car. By optimising the use of unoccupied car spaces, car-sharing is intended to reduce car traffic and combat pollution. Car-sharing was put on the agenda with the introduction of Urban Travel Plans (PDU) in 2000: the Urban Transport Authorities (AOTU) of conurbations with more than 100,000 inhabitants are required to encourage companies and public authorities to « draw up a mobility plan and encourage the transport of their staff, in particular through the use of public transport and car-sharing ». These mobility plans open up a car-sharing market for car-sharing companies that offer platform and management consultancy services directly to companies. The organisation of this car sharing is neither structured nor directed by the public authorities, but left to the responsibility and interpretation of the organisations (Delaunay, 2018).

Since the early 2010s, a third car-sharing regime has emerged: that of the resource car. In this way, « carpooling is becoming a public transport solution to fill gaps in the public transport supply » (Delaunay, 2018). Empty spaces in cars are seen as an untapped resource. In this vein, we recall the phrase already quoted in the introduction by the Minister for Transport, who refers to « 50 million empty seats » in circulation and therefore potentially carpoolable. The public authorities (State, local authorities, transport organising authorities) have thus increasingly invested in car sharing as an object of public action, for a variety of objectives that go beyond the issue of decarbonising transport. We have identified a number of objectives in the official statements of various public players, in their interventions in the media, in interviews and in car-sharing planning documents, which we have grouped into three categories:

-

Ecological objectives: to reduce the number of cars on the road and thus reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector (decarbonisation), air pollution and other environmental impacts;

-

Social objectives: to give non-motorised people access to mobility (accessibility), to reduce the energy vulnerability of households linked to income and the lack of alternatives to the car (social and territorial justice), to strengthen social links;

-

Optimising the mobility system: improving traffic flow (relieving congestion on the roads) and reducing costs for AOMs and mobility operators (savings on the transport budget).

Some of the objectives of car-sharing policies may also be contradictory, such as the desire to reduce car traffic while at the same time improving accessibility (which would generate new journeys).

A consensual and vague object of public action, constructed by default in relation to public transport.

« In a context of metropolisation and individualisation of lifestyles, demand for travel is intensifying, diversifying and calling into question the capacity of existing mobility systems to absorb this demand » (Delaunay, 2018). Car-sharing is developed in relation to public transport, either to compensate for its absence ("Car-sharing creates a shared mobility offer where there is no public transport" 4), or to complement it. It is then imagined as a means of supplementing timetables or relieving congestion on saturated routes. Some car-sharing services, such as car-sharing lines, are inspired by public transport and adopt its codes ("car-sharing like taking the bus" 5), or are even presented as a new form of public transport. In an interview with Le Monde in December 2022, the French Transport Minister said: « We potentially have a public transport network at our disposal » 6.

Car-sharing is often offered as an alternative to public transport, in areas where public transport is considered to be of little or no use. A technician from the Brittany Region reports: « On this line, the journey is made more quickly by car than by train, so rail services are not going to compete with solo car travel. Rail services will work for occasional journeys and tourism, but not for home-to-work journeys. That’s where we need to offer other solutions, such as car sharing ». This default framing, often due to a lack of solid data on carpooling practices, leads to the definition of vague carpooling massification targets. For example, in this AOM, which includes a metropolis: « We have a master plan with the objective of increasing the modal share of carpooling, and consequently eliminating a few vehicles. We don’t know how many, but we’ll assess it ». In this other local authority, also a metropolis, the modal share objective set out in the PDU is only a « horizon » according to the technician we met. For this operator, « most, or all, local authorities have little experience of car sharing, so they don’t really know what success or failure means. When we ask them at the start of the project what their objectives are, some will set a target of 200 journeys a month, others 10,000 a month ». The potential of car sharing is difficult for local authorities to define, and they consider it easy to deploy at first glance. It is an additional service that can be offered immediately, unlike a traditional public transport service.

Although it is a practice as old as the existence of the car, car-sharing is presented by the players we met as a modern solution. « Young people want to get around differently, buses are considered old-fashioned and inflexible », says one company employee 7 Car-sharing also has a consensual character, as described by Aurélien Bigo, a researcher into the energy transition in transport: « The occupancy rate is a slightly intermediate lever. It is being pushed both by scenarios focusing on sobriety, because carpooling implies a change in behaviour, and also by scenarios focusing on technology, because it makes it possible to optimise the automotive system without necessarily calling it into question. There is also the idea that car sharing can be helped by technological innovations. 8 This intermediate position helps to explain a form of consensus around car sharing that transcends ideological divides.

For a number of local authorities and public players, its deployment is bound to be beneficial. As a result, the relevance of car sharing is rarely, if ever, questioned. « We’ve never asked ourselves whether we should offer car sharing. Only one local authority in our region didn’t want it, but in general, car-sharing has a rather consensual aspect », reports a regional employee. Behind the promotion of car sharing, we find both local authorities with ambitious policies to reduce the use of cars and traditional players in the automotive sector. This consensual aspect is reflected in the players and local authorities we met for this study, which are presided over by different political parties.

Public authorities are now fully integrated into the business model of the main car-sharing operators.

From a seemingly profitable market to the need for public funding

Carpooling can be organised without intermediaries, and this is still the case for the majority of journeys made by carpoolers. The first attempt to institutionalise the collective and organised use of cars in France dates back to 1958, with the Allostop-Provoya association (Vincent, 2008). The association’s main aim was to enable people without cars, mainly students, to get around by sharing the journeys of people with cars. The association’s aim was to set up an « organised hitch-hiking service », and it subsequently helped to spread the term « car-sharing » in France (Vincent, 2008).

Later, in the 2000s, with the Internet taking its first steps, the first car-sharing websites were set up, and around sixty local car-sharing companies were created in France between 2000 and 2015 (Delaunay, 2018). They developed within the framework of a so-called « Business-to-Business » (B2B) business model, in which they were paid by the company or public organisation for their service offering, which consisted of providing a matchmaking platform and running awareness-raising campaigns for employees. However, this apparently profitable market is gradually collapsing, as users of « first-generation » planned car-sharing platforms are abandoning the platforms once the crews have been formed. They stop posting their journeys and the platforms gradually become obsolete.

Blablacar, created in 2006, was to shake up the car-sharing sector by succeeding in finding a profitable business model for long-distance car-sharing. The company helped to popularise long-distance car-sharing via a platform, and today has 90% of the market in France and 90 million users worldwide. Blablacar’s business model is different from the platforms mentioned above, since here it is a « Customer-to-Customer » (C2C) model. Consumers produce, exchange or consume goods or services directly between themselves, via a platform that brings them together. This is the principle on which the collaborative economy is based (Borel, 2015). Since 2011, Blablacar has made this business model profitable by charging a commission on each journey made on its platform 9. The model works for long-distance journeys, because sharing the cost for the driver represents an attractive economic gain, and the cost of the journey is often lower than that of the train. The average distance travelled with Blablacar is 239km 10.

However, such a model cannot be developed for everyday, short-distance journeys. Firstly, the regular nature of everyday carpooling means less dependence on the platform, since once formed, carpooling crews can organise themselves informally. Faced with this, operators have relied on technological advances to offer « dynamic » carpooling, making it possible to search for a potential driver or passenger even at the last minute. However, as T. Delaunay in his thesis, once again this car-sharing model has proved disappointing for economic players 11. The economic transactions between carpoolers are too small for operators to be able to charge a commission, and such a practice is not feasible even though the interest in carpooling for short journeys is much weaker than for long distances.

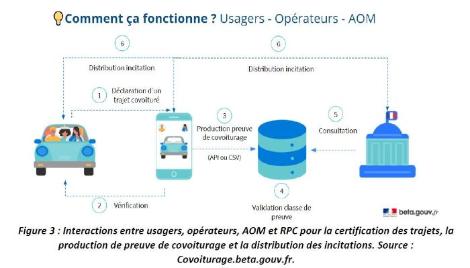

With the LOM, for which the operators were consulted and participated « quite a lot », a new opportunity will enable them to attract users to their platform and perpetuate their use: this involves the distribution by the AOMs of subsidies to drivers and/or passengers, the amount of which may exceed the costs incurred in making the journey. Before the LOM, the notion of sharing costs was paramount in the definition of car sharing, but now the AOMs can offer financial incentives to drivers and/or passengers. AOMs can also subsidise drivers who have offered a journey without finding a passenger (empty journeys). These two provisions are intended to encourage drivers to take part in car-sharing services. The AOM’s contribution varies according to the arrangements established, and whether or not the passenger contributes to the costs; some AOMs in fact offer free journeys for the passenger. The use of car-sharing platforms is essential in order to obtain these financial incentives. The financial incentives are distributed by the AOMs once proof of the carpooling journey has been produced by the Carpooling Proof Register (RPC). With the LOM, for which the operators were consulted and « participated quite a lot », a new opportunity will enable them to attract users to their platform and perpetuate their use: this involves the distribution by the AOMs of subsidies to drivers and/or passengers, the amount of which may exceed the costs incurred in making the journey. Before the LOM, the notion of sharing costs was paramount in the definition of car sharing, but now the AOMs can offer financial incentives to drivers and/or passengers. AOMs can also subsidise drivers who have offered a journey without finding a passenger (empty journeys). These two provisions are intended to encourage drivers to take part in car-sharing services. The AOM’s contribution varies according to the arrangements established, and whether or not the passenger contributes to the costs; some AOMs in fact offer free journeys for the passenger. The use of car-sharing platforms is essential in order to obtain these financial incentives.

The financial incentives are distributed by the AOMs once proof of the carpooling journey has been produced by the Carpooling Proof Register (RPC). The RPC has formed partnerships with 23 car-sharing operators 12. The RPC is presented as a « trusted third party » 13 between the operators and the AOMs to certify the journeys made. It should also make it possible to monitor car-sharing, with dynamic data feedback. This data is then published as open data and used by the Observatoire national du covoiturage du quotidien (observatoire.covoiturage.beta.gouv.fr/) to illustrate the level of intermediated carpooling in different regions. Their website opened at the end of 2021.

As well as funding the financial incentives for car sharing, the AOMs must also fund the car sharing operators for the services provided, in a B2G « Business to Government » business model. This funding takes the form of flat-rate financing, to which is sometimes added the financing of a commission for each journey made. Such a business model dependent on public funding is a far cry from the idealised vision of collaborative economy players free of state intermediaries, or more broadly public intermediaries 14. Whereas, for long-distance car-sharing, the main operator in this sector includes the commission in the charges paid by passengers, for everyday car-sharing, when there is a commission per journey, it is paid by the AOMs, and mechanisms largely financed by public money should make it possible to encourage people to use these car-sharing services.

The changes in the operators’ business model bear witness to the disillusionment that has plagued the short-distance car-sharing sector since the early 2000s. Far from being content to act as an intermediary between drivers and passengers, they have to turn to the public sector to obtain funding and, in particular, develop a model of financial incentives likely to keep users on their platform - and thus prevent car-sharing crews from organising themselves informally once they have been formed.

Diverse forms of carpooling and services involving varying degrees of support from an external intermediary

Today, car-sharing can be practised in a variety of ways and involves the intermediation of an external player to a greater or lesser extent. The first difference lies in the way the driver and passengers are brought together. Carpooling, as it is most commonly practised, is said to be planned, because the driver and passenger(s) agree before the journey on the time of departure, the pick-up point and the drop-off point. This carpooling can be « dynamic » if the matchmaking is organised at the last minute: thanks to geolocation technologies, the passenger can use the matchmaking service a few minutes before departure, and the driver can agree to share his journey at the last minute. This real-time contact should reduce the organisational workload involved in planning carpools.

A new form of carpooling, known as spontaneous carpooling, appeared in France in the 2010s. It follows the same logic as hitchhiking: the passenger goes to a specific point (a stop), positioned on a flow of traffic with drivers who can then choose to stop and pick up the passenger. The first forms of spontaneous car-sharing emerged in the United States in the mid-1970s, after the introduction of lanes reserved for « high-occupancy vehicles » (HOVs): slugging 15. In France, the Rezo Pouce association, in partnership with local authorities across France, has helped to extend « organised hitchhiking » networks across France: hitchhiking is organised around predetermined stops. The aim of the organised hitchhiking scheme was to make hitchhiking, a long-established but devalued practice, safer and more visible 16. This was followed by the introduction of car-sharing routes: stops were positioned along a route predefined in advance by the local authority and the operator. Spontaneous carpooling, while it can also be organised using matchmaking applications, relies above all on infrastructure intermediation: visible stops, illuminated signs indicating the presence of a passenger, stop layout, etc.

The second element of distinction lies in the degree of intermediation included in the contact. The most traditional and predominant format is informal contact, within circles of family, friends, professionals, neighbours, etc. Classic hitchhiking, on the other hand, is organised between strangers, but requires no outside intervention: on any given road, an individual can hold out his thumb and the driver can choose to stop. These carpooling or hitchhiking practices leave no trace and are therefore largely invisible to the public authorities, apart from through global mobility surveys.

There are very different models of car sharing intermediated by an external player or tool. Since the LOM, there has been one significant difference between these services that help carpoolers to get in touch with each other. Some of these services offer full monitoring of the carpooling relationship (identification and verification of the carpooler’s profile, geolocation of the journey, production of a proof of carpooling). This type of carpooling is necessary for the verification of the journey, by the Register of proofs of carpooling, for the distribution of financial incentives 17. In addition to the separation between informal and intermediated car sharing, there is also a boundary between incentivised car sharing (via the RPC’s partner platforms) and non-incentivised car sharing.

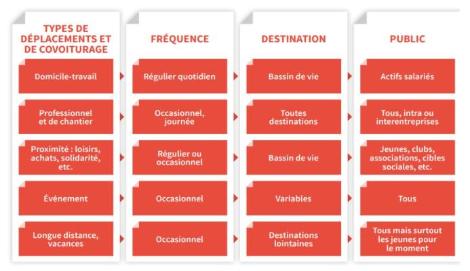

The tools used to put people in touch with each other are not always based on public players or companies. WhatsApp messaging services and Facebook groups dedicated to carpooling are numerous and active. The advertisements published on these groups often concern long-distance journeys, with the groups sometimes presenting themselves as an alternative to Blablacar (without commission and sometimes without any exchange of money). But there are also a myriad of local Facebook groups, whose members share journeys within a more or less extensive territorial area, from the region to a group of a few communes. In addition to social networks, groups of residents and associations are organising themselves to develop shared use of the car. For example, there are groups such as Perche Mobilités 18 and the Syndicat de la Montagne Limousine, which bring together local people who claim the territorial reality of an area divided between several administrative entities. In particular, these groups are proposing car sharing as a way of adapting to travel practices that are poorly or not at all covered by alternatives to the private car, notably because these travel areas do not correspond to administrative realities. Carpooling, whether planned or spontaneous, organised by an intermediary or informal, can be used for a variety of reasons. A diagram taken from the ADEME guide on short-distance carpooling (2017) distinguishes the main characteristics for each carpooling reason:

-

Home-to-work or home-to-study carpooling is the dominant reason for intermediated carpooling, for which the most initiatives can be found, whether at the level of operators (where critical mass is more easily achieved on this reason due to peak hours) or local authorities (particularly because self-driving is stronger there than for other reasons). Work-related carpooling is also used for business and site trips, by BPT professionals, people undergoing training or employees who need to travel to the same place (meeting, conference).

-

Local carpooling is also organised for more occasional journeys, such as leisure or shopping trips, for example the spontaneous carpooling routes set up by the Grand Chambery urban community to tourist destinations in the mountains. Carpooling can also be organised between parents, to share journeys to take children to their extra-curricular activities (KidrivOO, Hopinoy platforms, etc.).

-

Event-based carpooling is organised for one-off sports or cultural events. For example, cultural or sporting organisations link to car-sharing websites from their own pages (Ouestgo, Mobicoop), offer a plug-in to organise car-sharing via a service provider (covoiturage-simple, Yes we car event, TOGETZER, etc.) or develop their own car-sharing platform system >(note) 19]. Generalist car-sharing platforms also offer the possibility of creating events (Mobicoop’s « covievent » tool, for example). Finally, calls relayed in the media can support the informal organisation of carpooling to events or demonstrations 20.

Mechanisms for funding car sharing

The extension of the possibilities offered to local authorities to provide financial incentives for car-sharing services is in line with the desire of the Loi d’orientation des mobilités, enacted in 2019, to make car-sharing one of the « new solutions » that should be made « available to the greatest number of people, particularly in areas that are currently dependent on the private car. » 21 In particular, the LOM is based on the observation that « in 80% of the territory, no local authority offers a solution for everyday transport »; it therefore obliges all communities of communes to decide whether or not to take on the responsibility for mobility 22 - if they do, it is the Region that takes on the role of organising authority for local mobility, in addition to its role as regional AOM.

Thus, local AOMs and Regions are the two authorities designated by the LOM to put car sharing on the agenda. Historically, however, it has been the Départements that have taken up the issue, in particular by funding websites. Subsequently, some of these departmental sites have been integrated into regional platforms such as Mov’ici or OuestGo. However, the départements are continuing to invest in the subject, particularly in the area of car sharing areas, where there has been a real increase in activity and ambitious plans worth several million euros. Some départements, such as Aude and Hérault, are investing in carpooling via other areas of responsibility in addition to the management of departmental roads: social responsibilities (integration, solidarity), aid to communes, access to public services, etc.

In reality, all local authorities have powers that enable them to become involved, to a greater or lesser extent, in funding car-sharing policies: mobility, roads, social aid, etc. This public policy is also implemented on an inter-territorial scale, through structures such as metropolitan clusters, mixed mobility syndicates, regional nature parks, countries 23, etc.

There is a wide range of public and private players involved in financing car sharing. One of the main funding mechanisms is the Energy Savings Certificates (EEC) scheme, under which the French government obliges energy suppliers to make energy savings or to finance measures that enable them to do so. Of the CEE support programmes listed for energy-efficient mobility, 8 include car-sharing (car-sharing lines, rest areas, financial incentives, awareness campaigns), totalling €49 million 24. The main private financer of carpooling via CEE is Total Marketing France, with 5 out of 8 projects, 3 of which are co-financed with other private structures. In addition, €50 million from EWCs has been directly targeted to finance the bonus for first-time drivers under the Carpooling Plan 2023…

Employers (public and private) are invited to develop carpooling as a means of transport for their employees. The LOM has made available to employers a new financial scheme, the Forfait Mobilité Durable (FMD), which compensates the costs incurred by an employee travelling by bicycle, carpooling or using another clean means of transport25. The FMD is compulsory for civil service employees, with a maximum compensation of 400 euros per employee. In the private sector, on the other hand, it is optional: the employer decides whether to offer it, which modes of transport are eligible, and the amount and criteria for reimbursing expenses. The maximum amount of compensation is 800 euros per year per employee, exempt from tax and social security contributions 26. The FMD can be combined with reimbursement of public transport season tickets. According to the Baromètre du Forfait mobilité durable 2022, two out of five private employers have deployed the FMD, and of these, 56% have made carpooling eligible.

In addition, some companies are financing or developing their own platforms, in order to offer car-sharing services to their employees (via contracts signed directly with car-sharing operators, for example) or to their customers, such as certain sporting or cultural organisations 27. Private automotive companies are also getting involved in the car-sharing sector, including motorway management companies. Since 2021, the French government has required new motorway delegation agreements to include a minimum programme for the deployment of car-sharing areas. Motorway management companies may also be involved in the management of carpool lanes deployed on their network. Autoroute Tunnel Mont Blanc (ATMB) has co-financed a programme of incentives for carpoolers run by the Pôle Métropolitain du Genevois Français (PMGF), while Vinci Autoroute has launched a « Baromètre de l’autosolisme » in 2022, the result of video measurements on 13 routes on its motorway network. Another example of a player invested in the car industry is the oil company Total Energies, which has provided Blablacar Daily users with a fuel card.

The construction of public car-sharing policies resembles a local « bricolage », with various sources of funding and forms of inter-territorial or public-private governance. Several projects may be launched in the same area, making it difficult to identify all the initiatives.

In conclusion, various public and private players are involved in financing and/or organising car sharing. The main beneficiaries of all these actions are the users of carpooling incentives, via the RPC’s partner platforms. Informal car-pooling users only benefit from the provision of car-pooling areas and lanes reserved for car-pooling, or the Forfait mobilité durable if it is set up by their employer and the employer does not ask the employee to use an intermediation platform to verify the practice. However, car-sharing via a platform is still very much in the minority, as we will see in the next section on the potential of car-sharing. So can it be an effective way of combating car-pooling? How can it contribute to decarbonisation?

-

1 VINCI Autoroutes has published three editions of its Car-Pooling Barometer to date. The study is based on video measurements taken in collaboration with Cyclope.ai (artificial intelligence) on more than 1.5 million vehicles travelling on the Vinci Autoroutes network between 8am and 10am, near eleven French conurbations.

-

2 This figure was calculated by WWF France using data from Kantar media. (www.wwf.fr/vous-informer/actualites/lobsession-de-la-publicite-pour-les-suv )

-

3 Longuar Z., Nicolas J-P., Verry D., 2010, « Chaque Français émet en moyenne deux tonnes de CO2 par an pour effectuer ses déplacements », in Le Jeannic Th., Roussel Ph., François D (eds), La mobilité des Français, Panorama issu de l’enquête nationale transports et déplacements, 2008, La revue du CGDD, p. 163-176. In this document, local mobility is defined as all journeys made within a radius of less than 80km as the crow flies from the home, both during the week and at weekends.

-

4 According to the Ministry of Ecological Transition website « Le covoiturage en France, ses avantages et la réglementation en vigueur », ecologie.gouv.fr, consulted on 13/04/2023. www.ecologie.gouv.fr/covoiturage-en-france-avantages-et-reglementation-en-vigueur

-

5 This is the slogan of the operator Ecov.

-

7 Interview with a company

-

8 Interview with Aurélien Bigo, 06/22.

-

9 In addition, the covoiturage-libre website was created after BlaBlaCar’s decision: some of the users then left the platform and got together to create an association « to continue carpooling with a view to solidarity, ecology and, above all, without any commission on journeys ». Now a cooperative, covoiturage_libre joined forces with Covivo to become Mobicoop in 2018. (Source: Mobicoop.fr website)

-

10 Blog blablacar, « ETUDE - Le covoiturage permet d’économiser plus d’1,6 millions de tonnes de CO2 par an tout en doubler le nombre de personnes qui se déplace », March 2019. Accessed on 13/07/2022. blog.blablacar.fr/blablalife/lp/zeroemptyseats

-

11 This is what he presents in a diagram of car-sharing cycles: an initial peak of illusions driven by planned car-sharing (between early 2000 and 2010), followed by an initial phase of disillusionment, then a second peak of illusions driven by dynamic car-sharing (between 2012 and 2017) and finally a phase of disillusionment from 2017 onwards (Delaunay, 2018).

-

12 The list is available on the following page: covoiturage.beta.gouv.fr/operateurs/

-

13 RPC website covoiturage.beta.gouv.fr/

-

14 S. Borel, D. Massé and D. Demailly, (2015) show in « L’économie collaborative, entre utopie et big business » that one of the principles of collaborative economy players is the horizontality of modes of design, production and consumption. « This horizontality is synonymous with (more or less) direct coordination between individuals, and often benefits from the use of new information and communication technologies.

-

15 Slugging was organised spontaneously after the introduction of High-Occupancy Vehicle Lanes in the mid-1970s in major American cities with heavy car congestion. Slugging refers to the formation of car-sharing crews at or near stops along the lanes. The practice quickly became widespread in the United States: drivers save time by being able to use a reserved lane (thus avoiding congestion) and passengers can save travel time and money, as the service is free and not based on an exchange of money.

-

16 Several dozen experiments in organised hitchhiking have been conducted in France since 2010, and these were recorded between 2013 and 2019 by the autosBus association. It reports two trends: « many experiments have run out of steam and the majority of new networks are being created under the RezoPouce banner. » www.autosbus.org/tour-de-france

-

17 The Carpooling Plan’s driver bonus has nevertheless changed the situation slightly, by also including carpooling services that do not meet such criteria (OuestGo, Picholines, France Covoit’).

-

18 Perche Mobilités, created in 2021, defines itself as an interdepartmental association between Orne, Sarthe, Eure et Loir and Loir et Cher. Its aim is to « promote and encourage eco-responsible and shared mobility in the Perche region » www.perchemobilites.fr/

-

19 This is the case, for example, of the French Football Federation (FFF), which since March 2023 has been offering supporters a platform for organising their travel to matches (covoiturage.fff.fr/ ).

-

20 Le Télégramme relayed information about the organisation of car pooling to go to the demonstration on 6 April 2023 in Vannes against pension reform. (www.letelegramme.fr/morbihan/auray/d-auray-depart-en-covoiturage-pour-manifester-a-vannes-jeudi-6-avril-05-04-2023-13311559.php

-

21 www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/LOM%20-%20Nouvelles%20mobilit%C3%A9s.pdf

-

22 53% of the communities of communes have chosen to acquire mobility powers, becoming AOMs, while 47% have not.

-

23 This status, introduced in 1995, is the result of an initiative by a number of local authorities with geographical, economic, cultural or social cohesion within a catchment area or employment area.

-

24 According to data available on the France mobilités website, « Les certificats d’économies d’énergie pour les mobilités », www.francemobilites.fr/demarches-partenariales/cee-et-mobilites

-

25 Eligible modes are bicycles and electrically assisted bicycles (personal and rental); car-sharing (driver or passenger); personal mobility devices, mopeds and motorbikes for hire or self-service (such as free-floating scooters and electric scooters); car-sharing with electric, rechargeable hybrid or hydrogen-powered vehicles; public transport (excluding season tickets); personal motorised mobility devices (scooters, monoroues, gyropodes, skateboards, hoverboards, etc.). ..).

-

26 In excess of €800, the MDF is subject to tax and social security contributions.

-

27 This is the case, for example, with the French Football Federation (FFF), which since March 2023 has offered supporters a platform for organising their travel to matches (covoiturage.fff.fr/ ).