The « Ehop près de chez moi » experiment: local solidarity carpooling in Brittany

septembre 2023

Local carpooling was developed as an experiment between 2019 and 2022 by the Ehop association and three Breton EPCI volunteers with different profiles. This project, called « Ehop près de chez moi » (Ehop near me), has enabled a new form of carpooling to be tested, with the social objective of providing access to mobility for everyday activities (shopping, leisure, care). The way in which people are put in touch with each other, the approach taken and the type of journeys made differ from what is commonly set up by traditional car-sharing services. Cross-analysis and feedback from two of these EPCIs - the Concarneau Cornouaille Agglomération urban community and the Ploërmel Communauté community of communes - will enable us to assess this experiment in local carpooling based on solidarity.

People interviewed :

-

Ophélie Bigot, co-president of the Ehop association

-

Cédric Cherfils, Head of Mobility Studies and Projects, Brittany Region

-

Gérard Martin, Vice-Chairman, Mobility and Transport, Concarneau Cornouaille Conurbation; Benoît Bithorel, Head of Transport, Concarneau Conurbation and Susie Brenner, Transitions Coordinator, Concarneau Conurbation

-

Felix Moal, in charge of steering OuestGo for the Brittany Region

-

Florence Prunet, Vice-President of Mobility, Ploërmel Communauté and Jonathan Thiery, Mobility Officer, Ploërmel Communauté

Mobility issues in two EPCIs taking part in the « Ehop près de chez moi » experiment

The Concarneau Cornouaille Agglomération (CCA) conurbation community, located in Finistère, is an EPCI with a population of 50,000 spread across 9 communes, with an average population density of 137 inhabitants/km². Concarneau is the town centre, and the area is served by the TGV high-speed train from Rosporden, a member of the CCA. As a local AOM, the EPCI has been operating a « Coralie » transport network since 2012, which is well established in the area, with 4 regular bus routes, around ten transport on demand (TAD) routes, and a strong commitment to developing the cycling network. The school bus network is also accessible to all, but very little use is made of it. As a result, 80% of public transport users are « captives », and car use is easy in the EPCI’s communes, which is also linked to parking facilities in the communes, which are not under the jurisdiction of the Communauté d’agglomération.

Ploërmel Communauté is an EPCI with a population of 42,000, comprising 30 communes, including a central town (Ploërmel) where ¼ of the EPCI’s inhabitants live, a number of medium-sized centres and very small communes. It is a very large rural area (800 km²), with a low average population density (52 inhabitants/km²). As soon as the EPCI was created in 2017, the question of « how to create a community with such distances between communes » was raised. Despite the rural and sparsely populated nature of the area, mobility is one of the key areas of focus for the executive, to ensure balanced development of the area and maintain access to services and activities. The communauté de communes has become an AOM and since 2018 has been organising a range of mobility services through the Réseau intercommunal de voyage (RIV); 9 regular bus routes, zonal TAD, electric bike hire, car hire and car sharing. However, the car is still the dominant mode of transport, accounting for 84% of the kilometres travelled.

Promoting everyday car-sharing in Brittany through the involvement of the Ehop association, a « car-sharing activator », and several local authorities in the west of the region.

Brittany and the Loire-Atlantique region have been putting car sharing on the agenda for a long time, in particular by the departments of Finistère, Morbihan, Ille-et-Vilaine and Loire-Atlantique, and by the metropolitan areas of Rennes and Nantes. At the same time, the Allostop Bretagne association was set up in 1997, and in 2002 several local authorities supported the Covoiturage+ association, which aims to develop home-work carpooling in Ille-et-Vilaine, as reported in the case study of Rennes métropole and Covoiturage+ detailed in the ADEME-Inddigo report (2015). Car-pooling matches were initially managed in Excel by the association’s founders, and in 2004 the first website was launched. In 2013, the Ehop brand was created, reflecting « a shift towards helping people change their behaviour ». (Ehop website). In 2018, the Covoiturage+ association changed its name to Ehop and focused on its activity as a « car-sharing activator », in other words, for Ophélie Bigot, co-director of the association, an activity that « supports the development of public policies in terms of shared mobility. »

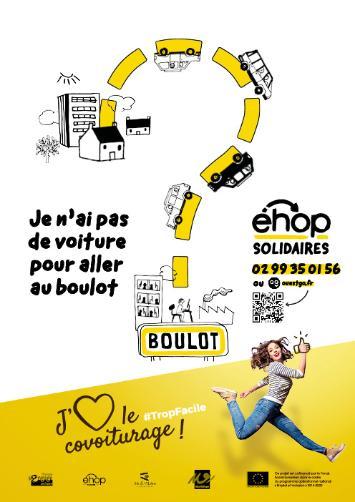

However, Ehop is still putting people in touch with each other through two services. Firstly, the « Ehop Solidaires » service, dedicated to helping people with a digital divide find employment or training. A telephone line is available for this service, and more than 950 applications were received in 2021. The second service is the « Ehop près de chez moi » (Ehop near me) experiment, which we will describe in more detail in the rest of this case study.

In 2016, Ehop and several local authorities joined forces to create the first regional public car-sharing platform: OuestGo. This shared platform is the result of cooperation between the Brittany Region, the Finistère Department, Rennes Métropole, Nantes Métropole, Brest Métropole, the CARENE St Nazaire Agglomération and the State (DREAL Bretagne), with the support of ADEME. On its website, OuestGo details the various principles of this collective initiative between local authorities (see box below). However, journeys made on OuestGo are not eligible for financial incentives. However, since 2023, OuestGo has been a partner of the RPC in obtaining the car-sharing scheme’s bonus for first-time drivers.

The emergence of the « Ehop près de chez moi » experiment: adapting the offer and support for carpooling to develop « an inclusive and intergenerational service for short local journeys ».

While Ehop was historically set up to promote home-to-work carpooling, from 2019 the association will be developing a carpooling experiment for other purposes: « Ehop près de chez moi ». Following a survey carried out in 2018 among 400 residents and six social structures in Concarneau Cornouaille agglomération and Ploërmel Communauté, unmet mobility needs were identified, for reasons other than work or study. Initially, the association assumed that the need was for families to take their children to extra-curricular activities, but informal networks were already in place to meet these needs. On the other hand, the survey showed that there was a need for local, very short-distance activities, such as going to the doctor or shopping, particularly for senior citizens. The survey also showed the importance of offering a service not only on a platform, but also with a telephone line to provide human support. The communication messages, the tools on offer and the target audience are all different from the dominant approach to home-work car sharing. The focus will be on local, « ultra-local » carpooling, to bring together residents from the same inter-municipality, or even the same commune or neighbourhood.

The « Ehop près de chez moi » experiment is being developed within three EPCIs and financed for 3 years by ADEME funding for Concarneau Cornouaille Agglomération and Ploërmel Communauté, and by aid from the Département d’Ille-et-Vilaine and the prefecture for the Communauté de communes Bretagne romantique. The two local authorities we met presented local carpooling as complementary to the bus services developed in their areas. « The observation that was made was that the transport network that has existed for 10 years now doesn’t allow you to go everywhere, and as we’re in a sparsely populated area, with scattered housing, there are isolated people », reports Benoit Bithorel, head of the transport department at the Concarneau CA. For Florence Prunet, Member of Parliament for Ploërmel Communauté, « car-sharing is seen as a complementary service, like other mobility services, because in rural areas, buses can’t pass every hour in every town ».

Ophélie Bigot, co-director of Ehop, describes the experiment as a social innovation, designed to reach the most isolated people with no mobility solution. Even though transport services exist in the two areas studied here (bus, TAD), they do not always meet needs, either in terms of timetables or geographical coverage, or because they are perceived as dangerous or uncomfortable. A study carried out by the Pays de la Loire Gérontopôle showed that in rural areas, 70% of senior citizens use cars and 25% walk. In general, if they can no longer use their car, they don’t replace it with another mode of transport and stop travelling. Even if public transport is available, they make little use of it, either because they don’t feel safe using it, or because the idea of freedom associated with the car is still very strong 1.

The solidarity aspect of the experiment is central, since no money is exchanged. Drivers are taking part as a service, to help each other out as neighbours or residents of the same area. « There’s the idea, for the driver, that I’m going to make this journey in any case, so if at the same time I can help out someone in my community who can’t get around, I’m going to help them. There really is this notion of mutual aid. I think it’s important in small communities to get back in touch with each other. In some areas, there are a lot of second homes, but given that they’re empty at the moment, the few elderly people who stay there are very happy to find people with whom they can chat and go for a drive », explains Gérard Martin, the mobility and transport councillor for Concarneau CA.

To sum up, the advantages put forward to promote this « local car-sharing » scheme are as follows:

-

Offering a new mobility solution that complements public transport;

-

Optimising journeys already made;

-

Breaking down social isolation;

-

Save money compared to the TAD 2.

Providing « human time » to experiment and « reach out » to isolated communities

There is a very real need to reach out to these isolated groups (the elderly, young people with no mobility solution), and to create a community of volunteers ready to help. Ehop has therefore sought out car-sharing referents in each community to act as a link and organise workshops. Regular events have been organised, particularly at markets and fairs, to recruit volunteer drivers. Passengers, on the other hand, tend to be recruited by the local network of structures in contact with isolated people (elected representatives, CCAS, PIJ, SIAE, etc.), with whom the latter have confidence. Communication campaigns have also been used to disseminate information about the scheme, highlighting a variety of reasons other than work or study.

Volunteer drivers can register their occasional or regular journeys on the dedicated website or by telephone, and passengers can make their requests in the same way. The association assists with all the contacts, and this human intermediation is a key element in this type of carpooling: « What came out of the experiment was that people appreciated being able to call, to have someone behind them to do the research to find available people, to check that the driver had decided to make the journey, to see if he or she would be available for the return journey…", explains Susie Brenner, transitions coordinator at Concarneau agglomération. Requesting journeys can be an opportunity for Ehop to present the mobility services that already exist in the area (bus, TAD) and that could meet the mobility needs. Similarly, the person dedicated to putting people in touch with people can also send out car-sharing « SOS » messages if there is a request for a journey without a solution, on social networks, via town halls, or even through the press if the need for travel is not urgent. « The association is giving « human time » to experiment. It’s a socially and environmentally useful project », says Ophélie Bigot, co-director of Ehop, because it aims to optimise existing car journeys in rural and suburban communities, while demonstrating solidarity and inclusiveness.

Results of three years of experimentation: a « solution of last resort » requiring a high level of human involvement and mobilisation of the local fabric

After 3 years of operation, Ehop organised round-table discussions in Rosporden on 15 November 2022, looking back over the 3 years of experimentation. The association reviewed the characteristics of the journeys made using its service: women are over-represented as drivers and passengers. The median age of passengers is 56, and 80% of passengers contacted the service by telephone, confirming the importance of intermediation and human support. The « ultra-local » nature of this carpooling is confirmed by the fact that one out of every two carpooling requests concerned local journeys of less than 10 km. Around a quarter of journeys were for health reasons, a quarter for shopping and a quarter for leisure. Lastly, 27% of requests were flexible in terms of times and dates.

In the end, 822 journeys were proposed by 500 drivers and 321 requests were made by 267 residents. 55% of the requests found a mobility solution, 68% of which involved carpooling, with the remainder satisfied by existing public transport services or the network of friends and family. The Concarneau CA shows an imbalance between drivers and passengers: 150 drivers and only 50 passengers took part in the programme. In the Ploërmel community, 91 requests for journeys were submitted and 23 connections were made. The average cost of each connection (which may involve several journeys) was €510. In comparison, the TAD service set up by Ploërmel Communauté, with an average of 550 journeys per week and a budget of €500,000 per year, costs €19 per journey. However, the target audience may be different.

However, the cost of the service must include all the activities carried out by the association, such as raising awareness among potential drivers on the ground, and providing mobility support for people who are unaware of existing solutions or for whom these solutions are unsuitable. Part of Ehop’s work also consists of promoting another tool, OuestGo, which is not included in the calculation of the cost per journey. For Florence Prunet, elected representative for mobility at Ploërmel Communauté, « these 23 connections pale in comparison with the work carried out by Ehop ». They are not indicative of Ehop’s awareness-raising work, the effects of which are not necessarily reflected in the number of journeys, according to the councillor: « Just because people don’t use Ehop doesn’t mean they don’t carpool. They may have been made aware of the service thanks to Ehop’s work, but they didn’t use it afterwards. F. Prunet describes how « we have to work very hard to reach as many people as possible. You have to get to know the people and appoint long-term contacts. She also notes the need to raise the profile of car-sharing, which is much less visible than a bus route that passes through a town.

The results of Ehop près de chez moi show that a great deal of effort has been put into running the scheme, recruiting volunteer drivers and passengers, and that the number of journeys made has been low. The association has made 6 recommendations after 3 years of experimentation:

-

Remain committed to supporting local residents. According to the association, there is a direct correlation between the number of public events and the effectiveness of the service. Local players need to be mobilised, as they are in a position to establish a relationship of trust that is likely to remove the obstacles inherent in car sharing;

-

Organising a service that is accessible to all, including residents with a digital divide: it is essential to offer a telephone hotline to put people in touch with each other and provide support;

-

The fact that this mobility solution, which complements transport services, cannot guarantee 100% of solutions. Local car-sharing is described as a solution of last resort, when the transport network or the network of contacts does not provide a solution;

-

Give local residents the time they need to make the most of this new service.

-

Design the service in line with the catchment area: travel practices transcend administrative boundaries;

-

Build up a solid base of driver carpoolers to be able to manage different carpooling requests in terms of regularity and anticipation.

The future of the « Ehop near me » scheme

In 2022, the local authorities taking part in the experiment have asked themselves whether the scheme should continue. Concarneau Cornouaille Agglomération has decided to bring the service in-house, dedicating a third of a full-time equivalent (FTE), or 12,000 euros a year, to running the telephone service and communicating about car-sharing and, beyond that, about mobility and transitions. Ploërmel Communauté has continued its partnership with Ehop, reducing the amount of time spent running the service and integrating it into the local authority’s remit. However, there are not enough resources to continue running the service and the community of volunteer carpoolers.

-

1 This example from the Gérontopole des Pays de la Loire study was mentioned by Pierre Grimaud, from CRESS Bretagne, at the round tables organised by Ehop in Rosporden on 15 November 2022.

-

2 These assets are described in the fact sheet « Looking back over 3 years of social innovation in Brittany 2019 - 2021 » distributed in Rosporden on 15/11/2022.