Delayed Processes and Specific Challenges: Urban renewal in East-Central European cities

Krisztina Keresztély, 2016

In East Central Europe, urban renewal has to tackle several specific challenges related to the particular development path of this part of the continent. In what measure are the challenges different from those faced by Western European countries? Is it possible to delineate an ‘Eastern European paradigm’ of urban renewal on the model of the Western European paradigm (see the analysis sheet) as described by Musterd and Ostendorf (2008) ?

East Central Europe – a geographical, political and socio-cultural concept

When speaking about this specific region situated between the western and eastern parts of Europe, we speak about a region that is characterised by a particular and extremely complex political and economic path and cultural identity. Already the delimitation of the geographical area gives a complex picture, by the overlapping of several regions. To go from the broader to the narrower terms:

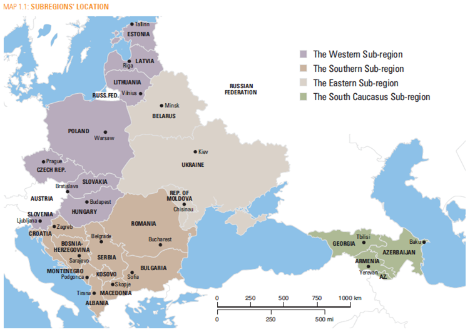

Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) has been used since the political transition of 1989 to designate all countries of Central Europe, South-Eastern Europe, and Eastern Europe, the common feature being the fact that they were subjected to communist regimes between WW2 and the collapse of the Iron Curtain. This area does not cover the former states of the Soviet Union (Commonwealth of Independent States). CEE countries are also described by the UN as the ‘Transition countries’, states which have achieved different levels of political democracy since 1990, from competitive democracies to war-torn political regimes (UN Habitat, 2013).

East-Central Europe (Europe Médiane) is part of this larger CEE region. It covers the countries situated between the German-speaking regions and the Russian territories. As a result it is designated as the region between the two Europes (‘la région de l’entre-deux’), being at the intersection of East and West. Unlike other CEE countries, East-Central European countries are also linked by their common cultural identities influenced by the Central European cultural and geopolitical area associated with the former German and Austrian-Hungarian Empires. Further, the East-Central European region more or less covers the area of the ‘New Europe’, countries that have joined the European Union since 2004.

The delayed emergence of the concept of urban renewal

Urban renewal is a relatively recent concept in East-Central Europe. In some countries, such as Hungary, Poland or the Czech Republic, the concept of physical urban renovation has appeared since the early 1990s in some of the main cities. In Hungary, even earlier, in the 1980s, a pilot urban renewal program had been launched by the state authorities in one block of housing in the city centre of Budapest. Former East Germany (German Democratic Republic, GDR) is an exception; here a western type of institutional and planning system was introduced soon after the unification of the two German countries. As a result, the strategic renewal of shrinking cities of the former GDR had been financed since the end of the 1990s by European and national funds (URBAN, Sozialestadt, etc.) and thus urban renewal followed similar principles as in Western European countries (Fayman, Keresztély et al., 2007) (see Leipzig’s case study sheet).

These differences notwithstanding, and contrary to the Western European states, urban renewal in East-Central European countries did not appear as a strategic policy at the city or national levels until European integration, or even later. Urban renewal was mainly understood as a physical intervention in certain parts of the city, aimed at the regeneration of an urban area by physically upgrading it and making it more economically viable and attractive to tourists. Even in areas where urban renewal appears as part of a development strategy at the city level, a lack of financial tools prevented systemic realisation of these programmes - as was the case in Budapest, Hungary (Fayman, Keresztély, Tomay, 2008). In the countries situated on the Eastern edges of the region, such as the Baltic States, Romania and Bulgaria, urban renewal remained a practically unknown concept until European integration (Fayman, Keresztély, et al., 2009).

How could we explain the lack of – or at least the considerable delay in the emergence of – any political will to introduce urban renewal as part of urban development in these cities that had for several decades suffered an increasingly advanced dilapidation of the built and the social environment? What are those special conditions that prevented the development of a global vision of urban development?

Countries ‘in transition’: phases of urban renewal

Urban renewal was in a way ‘incompatible’ with the dominant trends of politics as exercised in most of the East Central European countries - not only under the state socialist system, but also during the first decades following the political transition and, to some extent, even today. There are also significant differences between the countries, depending on the specific local conditions of urban development. Detailed country-to-country research on the situation is still not available; here we will try to draw an outline of the main phases of urban renewal as they occurred in the region and in some of its countries.

Instead of ‘phases’ one should use the term ‘typology’ as especially the two last types may exist in parallel, at the same time.

The typology depends on different factors such as:

-

Political and economic backgrounds;

-

Structure of the housing ownership, housing policies;

-

Characteristics of general urban policies, the role of different stakeholders and the main financial structures/sources.

1. Socialist urban renewal

The first type of urban renewal can be called ‘socialist urban renewal’ – not because of its ‘social’ character but because it appeared during the last years of the state socialist system. Urban renewal was almost non-existent under socialism, since the principle of renewal was ab ovo contradictory to the principles of the socialist type of urban renewal, strongly subordinated to the industry of (prefabricated) housing construction. Historical inner city areas became extremely abandoned and rundown even in cities where these districts had survived WWII (Budapest, Krakow, Prague, etc.). Further, urban development plans of the 1960s- early 1970s foresaw the demolishing of historical districts, and even though these plans were not put in practice in the majority of the cities, these areas remained untouched during the whole period of state socialism. The socialist type of urban renewal is therefore a rather limited phenomenon in terms of both geographical spread and impact on cities.

Hungary was the only country to attempt a systemic/planned rehabilitation regarded as part of urban development. This took place in the late 1970s. A state decision representing a surprisingly modern approach to urban development had been adopted in 1978 prescribing the rehabilitation of the whole inner city of Budapest – just at the same time similar decisions were adopted in the case of Vienna as well. The pilot - and finally the only - rehabilitation program was implemented in one specific block of residential buildings in the historical Jewish quarter of Budapest. The ‘socialist’ character of the program mainly resided in its financial and organizational structure: the rehabilitation took place in public owned real estate on public owned land, mainly with public financing, following a centrally adopted plan. The dwellers of the buildings concerned by the program were tenants of public housing. Thus the rehabilitation program was not ‘hampered’ by any clashes between stakeholders’ interests, and it was not supported by any private sector funding. The intervention had however some typical – although very limited – impacts of a more market-based urban renewal program: it generated a limited social mix as one-third of the new flats was occupied after the renovation by middle class party civil servants (and the other two-thirds by people who had been living in the district previously). These first results notwithstanding, the financial and political feasibility of the program turned out to be unrealistic: in the given structure rehabilitation was extremely costly and slow, and according to some estimates, at that pace renovation of the entire inner city could have taken 400 years1.

Apart from this specific experience, in the majority of the countries, renewal or rehabilitation concerned exclusively the renovation of buildings classified as part of the historical and cultural heritage. The renovation works were managed by special state-owned companies, such as Pracownie Konserwacji Zabytków – PKZ in Poland. In the case of renovation works, these companies decided where the buildings’ dwellers would go 2.

2. Market-based urban renewal

The second type (phase) of urban renewal, which can be described as ‘market-based urban renewal’, appeared after the political transition and introduction of market-based economies in CEE countries (1989/90). This is a large group containing a great variety of interventions, with changing patterns of objectives, stakeholders, financial structures and political willingness, but characterized by some common elements, especially the prevalence of private financing and the relatively weak impact of urban planning and regulation. This fact does not exclude of course the existence of programs with the engagement of the public sector. But as a general rule, we cannot speak about any systemic, strategically planned patterns of urban renewal, only about sporadic interventions, with two important common characteristics. First, all interventions are subordinated to market-based interests (even in the case of the public sector’s initiatives) and their main outcome is the increased attractiveness of the city (or the given neighborhood), and, as a result, gentrification. Second, almost all interventions are limited to physical renovation/renewal, while all other factors (social, cultural, environmental, global urban) remain secondary, and often completely neglected.

Market-based urban renewal in East-Central European countries has also been strongly determined by some specific features linked to the transition of these countries and their cities from a state-led system to a decentralized and market-oriented one. The most important among these processes was the reform of the housing system introduced in all countries albeit with slight differences in character and timing.

Housing reform was in fact based on two parallel processes.

-

The first process is decentralization, or the transfer of public housing stock and the main responsibilities for housing policies from the central state level to local governments. This process was launched everywhere as a sign of political transition, but the scale remained different in each country. For instance, in Hungary (see the case studies sheets on Corvin Promenade and Magdolna neighbourhood), the transfer concerned the entire state-owned housing stock, while in other countries, only part of it. In the Czech Republic (see the case studies sheets on Ostrava and Brno), the transfer concerned only the state-owned dwellings built after 1948 – thus approximately 28% of the total stock (Pichler-Milanovich, 1994). Former East Germany was a specific case, as here local authorities were already owners of the housing stock at the moment of the transition (see Liepzig’s case study).

-

The second process is housing privatization, introduced in rather different ways according to the different national policies. In some countries, as in in Hungary (see the case studies sheets on Corvin Promenade and Magdolna neighbourhood), for instance, privatization concerned the entire public housing stock: local governments were obliged, by the law, to sell their entire stock to their tenants at very advantageous price. In other countries, as in Poland, privatization concerned only a limited number of flats and it was preceded by the restitution of housing units confiscated from Jewish families during WWII.

The above processes took place in countries where the notion of ownership and tenancy was rather different than in the Western European context. In reality, the state socialist system had been much more nuanced than we might imagine it today, and as stated by Hegedűs et al. (2013) “Privatization and restitution thus took place in a housing system where, in practice, public ownership was closer to a quasi-private ownership.” The boundaries between renting and owning had been blurred in several cases during communism: for instance, through the creation of housing cooperatives where members had practically the same rights as owners (an often used solution in Poland, as well as in Hungary during the 1970s and 1980s), or through the possibility of inheriting tenancy rights (Hungary, Latvia) (Hegedűs et al., 2013), or through the increasing number of single family houses, often built by the inhabitants themselves.

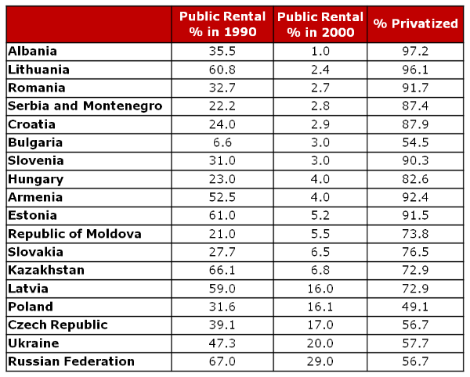

As a result of decentralization and privatization, housing stock, basic element of urban renewal, has been dispersed. Housing ownership increased everywhere and public rental diminished, although the pace of this change differed according to the countries: from a rather moderate decrease as in Poland, the Czech Republic or Ukraine to a more radical fall, as in Hungary or Slovenia, or an extreme drop, as in Lithuania, Estonia, etc. (see table 1)

Hegedűs et al. (2013), p.39.

Source: UN-ECE (2002); Hegedüs and Struyk (2005).

This development has a particular importance regarding urban renewal, and run-down inner city areas were affected in a specific way. While a growing number of inhabitants became owners of their housing, they often had no further capacities to contribute to the renewal of the common parts of the condominiums. As a result of privatization, local governments’ competencies for physical intervention were in most cases limited to interventions in public areas, streets, squares, public buildings etc., while they had practically no capacities to support housing renovation. Further, at that time, and especially during the 1990s, the social and other ‘soft’ elements of urban renewal were not regarded as really ‘serious’ elements of the urban planning process… A kind of late liberalist policy appeared in Central Eastern European cities, that was a logical step after the highly centralized system, but that was also related to similar tendencies in other parts or Europe.

In this context of East Central European countries joining the European Union during the 2000s, urban renewal was characterized as follows at the moment of their EU integration:

-

The lack of strategic planning with regard to urban renewal was a typical feature in almost all countries. The first city to prepare its urban renewal strategy was Budapest (1998). But in the majority of cases, such documents have only been written following European integration and the adoption of the European urban agenda in these countries. In Krakow for instance, a similar document was adopted in 2008. These strategies often were not based on any stronger political will, and were not underpinned by any larger, national level policies regarding urban development. As a result, their tools and possible effects remained limited or undefined.

-

Urban renewal was considered an action aimed at the gentrification of urban areas – gentrification being understood as a positive phenomenon, and in the majority of cases, it is limited to private interventions, such as the construction of new condominiums in former industrial or run down neighborhoods (Fayman, S., Keresztély, K., & Tomay, K., 2008).

This approach may also be understood as the result of the economic weakness of local governments. The latter made concessions on behalf of private investors whose intervention was needed to ‘bring up’ the poor inner city neighbourhoods. Supple building codes were established in order to attract investments. As a result, the typical ‘rehabilitation’ of this period was based on demolition and the erection of new buildings (Csanádi et al., 2007). Since many of these urban revitalization processes were not based on a previous programming/planning phase, they could more truthfully be referred to as ‘spontaneous’ urban regeneration. The lack of comprehensive strategy and competencies of the public sector have also resulted in extremely negative examples, often coupled with corruption, and the dramatic transformation of certain historical areas in cities (for instance, in parts of the historical Jewish neighborhoods of Budapest, Krakow, etc) (Keresztély, 2009). Yet in some other cases urban renewal interventions were based on more systemic planning, and still caused serious harm to the historical built heritage (Keresztély, 2009; Fayman et al., 2009). (See the Corvin Promenade case study sheet)

The public sector’s intervention remained thus mainly limited to the revitalization of public spaces: streets, squares, etc. The main objective of these interventions was the improvement of the city’s competencies in terms of attraction of tourists and investors. In some cases these interventions have had rather positive effects on the cities, reconverting rundown grey streets into streets with lively cultural life (Budapest, Krakow and many other cities during the 1990s and 2000s). In Prague these policies led to the revitalization of the whole inner city, which became the number one destination for western tourists wishing to discover one of the cities coming out from the communist system (Keresztély, 2009; Fayman et al., 2009) in ‘safe’ conditions.

As seen above, local governments (cities and districts) remained the main stakeholders of urban renewal, in cooperation with the private sector, whereas state level interventions in urban renewal remained rare and sporadic. One specific exception is the energy saving renewal of large housing estates. The first national level renovation programmes that have appeared since the 1990s were designated for the physical renovation of prefabricated housing estates. These programmes, especially in the first period, did not involve any specific social element. Nevertheless, they had some important indirect effects on the inhabitants of these housing estates, by improving their living conditions in aesthetic as well as economic terms. Most of the improvements had to do with energy renovation of certain elements of the buildings: replacing windows and reinforcing insulation. The importance of these programmes is undoubted: in East-Central Europe, around 20 to 40 percent of the housing stock is located in these housing estates (as opposed to 3-4 percent in Western European countries), housing around 170 million people (Egedy, T., 2007).

Apart from the above mentioned exception, urban renewal in that period had but very few interventions for the renovation of the existing housing stock. Among the very few examples for this kind of strategic urban renewal, one has to mention the case of middle Ferencváros in Budapest. Here a systemic urban renewal was launched right after the political transition, with strong support from the French Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (CDC). The latter, together with the local municipality, created a company of mixed ownership (Société d’économie mixte), and launched step-by-step renovation of the buildings. The main pre-condition of this process was that the district of Ferencváros did not launch any housing privatization in the rehabilitation area; thus the majority of the housing units remained in public ownership. The tenants could have been moved out of the area for the time of the renovation, and only those who could afford the increased rent could resettle in their former flats. A significant portion of the buildings was erased and new buildings constructed and the flats sold. The revenues generated in that way permitted the advancing of the project to further blocks of buildings. The area of middle Ferencváros that previously had been populated mostly by very disadvantaged families, many of them Roma people, has entirely changed its allure, into a green area where middle class families live…

3. Integrated Urban Renewal – discourse or reality?

In many East-Central European countries, urban renewal only appeared as a strategic challenge of urban development as a result of the countries’ joining the European Union. European funds and programmes became the crucial element of the financing of urban and regional development in these countries, where public funds are traditionally weak. Since the 2007-2013 planning period, integrated urban development has been a basic element of the European urban agenda (see the analysis sheet), and as such the preparation of integrated urban strategies became the precondition of the allocation of any financial support for local development projects. Amongst other aspects, integrated planning meant the introduction of participative processes in urban development: forums and community planning procedures with the involvement of local stakeholders, NGOs, inhabitants’ associations, local entrepreneurs, etc.

In new member states of the EU that were not eligible for pre-2004 programs promoting integrated urban development (especially, URBAN and URBACT I), integrated strategies were elaborated as the mandatory conditions of eligibility for structural funds with practically no previous experiences in any integrated approach to urban development. As a result, the articulation of several elements of urban renewal programs is different in the East-Central European experiences than in the Western European ones.

This basically top-down introduction of integrated planning had positive and negative consequences on the neighbourhoods. One positive consequence was the relative opening of urban planning methods to a more integrated vision of urban development and urban renewal, where social, environmental and cultural elements appear as crucial as those of the development of the physical, built environment. This process also means the approaching of these countries to the Western European paradigm on integrated urban renewal. On the other hand, the overwhelming role of the European programs in the financing of local development projects in cities has led to a certain uniformisation of these programmes. As mentioned above, in the majority of the countries, national and local level urban and housing policies and strategies were lacking. As a result, the European agenda became in many cases the only reference point with no real need of coordination with any other local policies and interests. The stakeholders who are active in these programmes – the municipality, local enterprises, NGOs etc. – only have to report their activities to the European authorities, and are not required to mesh with any complementary strategies, plans, or regulations. Also, the programmes financed on the European level (ERDF, ESF) are in most cases not complementary with other local or national level strategies and interventions. For instance, a neighbourhood-level socially integrated urban renewal program is often not completed by any locally financed housing renovation program. The result is what we can observe in the cases of Budapest or Brno: as the EU funds can only partly cover the housing element (only the renovation of some common areas and the facades, but not the flats for instance), the renovation of the facades of the buildings is not accompanied by renovation of the inside, or the flats from another public resource. The result is unsatisfied tenants, growing tensions between them and the local authorities, frustration of all partners and, overall, a lack of integrated and socially sensitive urban development.

In some extreme cases, integrated urban renewal projects may also cover contradictory political orientations: instead of reinforcing local integration, it can also cover policies enhancing the delocalisation and expulsion of marginal groups living in an area (see the case study on Budapest neighbourhoods of Magdolna and Corvin Promenade).

Conclusion: Specific Challenges for Integrated Urban Renewal in East Central Europe

Notwithstanding the label of ‘integrated development’, urban renewal in East-Central Europe is characterised by some specific features that are the result of the particular social and political development of this region. The challenges that integrated urban development faces in this part of Europe are slightly different from those evoked in Western European experience (see the analysis sheet and linked dossiers). Studies and analyses of these differences and specificities are as yet very fragmented, calling for further investigation and reflection. Here we try to point out some elements of the special East-Central European challenges for eventually launching further debate on these issues.

Several decades of state communism were characterised by the lack of any strategic intervention for the revitalisation of existing neighbourhoods. Then after the political transition the best located neighbourhoods became the subject of spontaneous development based on market-oriented investments, without any strategic urban renewal intervention. This led to a dramatic gentrification of these areas and, as a result, segregated urban areas have been partly and increasingly concentrated in smaller enclaves within cities, and partly pushed from the centre to the boundaries of cities (Ladányi, J., 2008). In East-Central European cities patterns of segregation are thus slightly different than in Western Europe – a phenomenon that is related to the historical development of cities. Segregation has to be understood in social terms, since in East-Central Europe, ethnic segregation is first of all related to the concentration of Roma population, while there has always been less immigration here than in western countries. Urban renewal programs therefore need to focus on different urban spaces and different social groups than in Western European cities.

Contrary to Western European countries, in East-Central Europe there has been practically no state level policy determining urban development, urban renewal, social integration and social housing. In some countries, attempts had been made basically on local – city – levels. But as a general rule, neo-liberal state policies remained dominant until recently, although EU integration and the access to structural funds introduced new requirements in terms of the preparation of local strategies for integrated development in all countries.

In the transition countries, the idea of social mixing practically did not appear, or if it did, it was mainly part of the ‘official discourse’ following European cohesion. The reasons are two-fold. First, in most of the countries the social element of urban renewal appeared very late, in general only after 2004. One often-mentioned exception is Hungary, where the first program based on the concept of social rehabilitation was worked out in the beginning of the 2000s, and gave birth to the first concrete program based on social participation in one of the most segregated urban areas of the city. Yet even in this case, public participation remained doubtful, and social mixing, although mentioned in the political discourse, has been translated in practice to conscious gentrification (see the Magdolna case study sheet). In light of the current debates on social mixing in Western Europe, opportunities for rearticulating these methods in the Central Eastern European regions so as to prevent further mistakes should be a topic for professional debate.

Another specificity is the traditionally relative weakness of the civil sector and civil participation in post-communist countries3 . Until the 2000s, in contrast with the hope that the birth of new democracies would bring a rapid spread of civil participation, the role of civil society remained relatively weak and the speed of development of ‘civil skills’ was less than ideal (Howard, 2002). This lack of civil skills and participation also explains the misuse of some principles of public participation in urban renewal projects – by local authorities as well as by civil society. There may, however, have been a positive change in the last decade. First, a new generation of activists and experts in social issues has grown up, with stronger know-how in civic skills thanks to their studies and/or practical experiences. Second, in some cases a growing number of local citizens are increasingly conscious about their rights and possible ways of action. On the basis of the case studies collected in the present dossier, the following types of civil participation can be identified:

-

civil associations appearing as stakeholders representing sectoral activities (culture, sport, housing etc.) either in an organised way (Leipzig) or as part of spontaneous urban regeneration processes (Podgorze in Krakow)

-

‘organised’ participation of the civil society in general in the frame of an integrated urban renewal project (Cejl in Brno, Magdolna in Budapest)

-

intervention of the civil society appearing in the form of protest actions (Matache in Bucharest)

-

a pro-active intervention where civil initiative may also change the way of development (Supilinn in Tartu)

1 Iván Tosics, paper presented at the Conference on the SEM IX rehabilitation program in Ferencváros, Institut Français de Budapest, November 23-24, 2015.

2 Urban renewal of Central European cities, such as Krakow in Poland.

3 To go further on this issue, see Cristian Pîrvulescu’s interview on participatoty democratie un Romania.

Sources

-

Csanádi, G., Csizmady, A., Kőszeghy, L., & Tomay, K., 2007, “A városrehabilitáció társadalmi hatásai Budapesten” (Social Effects of Urban Renewal in Budapest). in Enyedi, Gy. (ed.), A történelmi városközpontok átalakulásának társadalmi hatásai (Social Effects of the Transformation of Historical Inner City Neighbourhoods), MTA Társadalomkutató Központ, Budapest, p.93-118.

-

Egedy, T., 2007, “Lakótelep? Lakópark?” (Housing estate? Housing condominium?), A Földgömb, 25/4, pp. 34-45.

-

Fayman, S., Keresztély, K., & Krisjane, Z., 2009, « Les politiques de renouvellement urbain des villes d’Europe Centrale illustrées par la réhabilitation de quartiers existants – le cas de la ville de Riga en Lettonie », Final Report, manuscript, ACT Consultants, Anah-CDC, Paris.

-

Fayman, S., Keresztély, K., & Murzyn-Kupisz, M., 2009, « Les politiques de renouvellement urbain des villes d’Europe Centrale illustrées par la réhabilitation de quartiers existants – le cas de la ville de Cracovie en Pologne », Final Report, manuscript, ACT Consultants, Anah-CDC, Paris.

-

Fayman, S., Keresztély, K., & Tomay, K., 2008, « Les politiques de renouvellement urbain des villes d’Europe Centrale illustrées par la réhabilitation de quartiers existants – le cas de la ville de Budapest en Hongrie », Final Report, manuscript, ACT Consultants, Anah-CDC, Paris.

-

Fayman, S., Keresztély, K., Trostorff, B. Goltz, E. & Lenk, S., 2007, « Les politiques de renouvellement urbain des villes d’Europe Centrale illustrées par la réhabilitation de quartiers existants – le cas de la ville de Leipzig en Allemagne », Final Report, manuscript, ACT Consultants, Anah-CDC, Paris.

-

Hegedüs, J., Lux, M., & Teller, N. (eds.), 2013, Social Housing in Transition Countries. New York, London: Routledge, 343 p.

-

Howard, M.M., 2002, “The Weakness of Postcommunist Civil Society”, Journal of Democracy, Volume 13, Number 1, January 2002, pp. 157-169.

-

Kährik, A., & Tammaru, T., 2010, “Soviet Prefabricated Panel Housing Estates: Areas of Continued Social Mix or Decline? The Case of Tallinn”, Housing Studies Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 201–219.

-

Keresztély, K., 2012, “The Impact of the Crisis on Housing and ‘Urban renewal in Budapest’”, in Housing in Europe: Time to Evict the Crisis, Passerelle special issue, N°7, October 2012, AITEC / Coredem, France, pp. 41-48.

-

Keresztély, K. & W. Scott, J., 2012, “Urban Regeneration in the Post-Socialist Context: Budapest and the Search for a Social Dimension”, European Planning Studies, Vol 20, Issue 7: “Urban Change and Urban Regeneration Strategies in Central East Europe”, p. 111-1134.

-

Keresztély, K., 2009, “Wasting Memories – Gentrification vs. Urban Values in the Jewish Neighbourhood of Budapest”, in Murzy-Kupisz M. & Purchla J. (eds), Reclaiming Memory, Urban Regeneration in the Historic Jewish Quarters in Central European Cities, International Cultural Centre, Krakow, p.163 – 180.

-

Ladányi, J., 2008, Lakóhelyi szegregáció Budapesten (Residential segregation in Budapest), ÚMK Budapest.

-

Musterd, S. & Ostendorf, W., 2008, « Integrated urban renewal in The Netherlands: a critical appraisal », Urban Research & Practice, 1:1, p.78-92.

-

Pichler-Milanovich, N., 1994, “The role of housing policy in the transformation process of Central-East European cities”, Urban Studies, vol. 31, n°7, pp. 1097-1115.

-

Saisset P., 2014, La Hongrie post-communiste comme opportunité: de la diffusion à l’abandon des modèles d’interventions urbaines de la Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, Master thesis, EHESS, France.

-

Sykora, L., 2005, Gentrification in post-communist cities, in Atkinson, R. & Bridget, G. (eds.), Gentrification in a Global Context, Routledge, pp. 91-106.

-

UN Habitat, 2013, The State of European Cities in Transition 2013. Taking stock after 20 years of reform. Regional State of the Cities Reports, 250 p.