The Climate Conferences - Deepening action through public and private investment and regulation

Lessons from the 6th session

Pierre Calame, Armel Prieur, mars 2021

In the face of global warming, how can we move towards an obligation of result? This is what is at stake in this series of public debates, which will allow us to become familiar with the idea of an obligation to achieve results, to explore the various possible ways of meeting this obligation and to question the public authorities on how to assume their responsibilities in this respect.

This sixth session of the Assises is devoted to examining the second family1 of solutions for dealing with global warming, the one that combines a fairly complete set of sectoral policies, public investments, regulations, bank commitments and technical innovations. This is the oldest family of solutions, dating back to the national Agendas 21 resulting from the 1992 Earth Summit, but also the one that remains dominant today in state and European policies.

À télécharger : edouardbouin_si_le_climat_etait_une_banque.pdf (410 Kio), quirion_providing_decent_living_with_minimum_energy.pdf (2,2 Mio), under_reporting_of_greenhouse_gas_emissions_in_us_cities.pdf (1,1 Mio)

Traditionally, for the reasons mentioned in the previous sessions, these policies have focused on « territorial » emissions, on national or European soil, but more recently they are opening up to take into account imported energy and the whole of our societies’ ecological footprint.

The speakers were very varied and time was given to interventions from the floor.

Main speakers :

-

Antoine Colombani, former ENA student, adviser to the Vice-President of the European Commission in charge of the Green Pact, Frans Timmermans;

-

Édouard Bouin, representative of the association Agir pour le climat ;

-

Benoît Lebot, former president and member of the association NégaWatt, engineer, with a long experience of accompanying energy efficiency policies in G20 countries ;

-

Philippe Quirion, President of the Climate Action Network (RAC - France), researcher at the CIRED, research director at the CNRS ;

-

Anne Rostaing, President of the Coopérative Carbone de la Rochelle ;

-

Alexis Normand, founder of Greenly ;

-

Denis Bonnelle, retired professor and member of Observ’ER

Also speaking from the floor :

-

Raymond Zaharia, former CNES engineer, very involved with the Citizens’ Climate Convention ; #Ref. err: person/1250#Denis Bonnelle, retired professor and member of Observ’ER.

-

Murielle Raulic and Guy Kulitza, members of the Citizens’ Climate Convention

-

Michel Cucchi, hospital director

-

and Denis Pechin, retired engineer from the automobile industry.

This session, like the previous one, examined the scope and limits of this family of solutions, based on four questions, common to sessions 4, 5, 6 and 7 :

-

A/ Capping and obligation to achieve results : how can the total carbon footprint of society be reduced at a defined annual rate, which implies rationing the fossil energy corresponding to this footprint ?

-

B/ How can we take into account, as part of the responsibility of our societies with regard to climate change, the total footprint of society and not only the footprints emitted on our soil (the latest report of the Ministry of Ecological Transition, dated December 2020, estimates that the GHG footprint of the French is about ten tons of CO2 equivalent per inhabitant, 54% of which are « imported » emissions)?

-

C/ How can we reconcile the fight against global warming with social justice; how can we ensure the decoupling of the well-being of all from fossil energy consumption?

-

D/ How to mobilise all actors around common objectives ?

Given that these solutions have been put forward for a long time without ever having achieved the objectives assigned to them, Pierre Calame asked everyone to say what made them think that, this time, the results would be up to the task.

The lessons of the session are classified by question, after briefly recalling the general perspective presented by each of the speakers.

-

Antoine Colombani recalled that the European Union was in the final stages of drafting and adopting a climate law, currently being debated within the institutions, which sets a target of carbon neutrality by 2050 and a reduction of at least 55% of emissions by 2030. The preferred tools are investments, allowances allocated to high-emitting companies (extension of the EU ETS) and a wide range of regulatory measures.

-

Benoît Lebot outlined the energy transition scenario drawn up by the association NégaWatt for the period 2017 - 2050. It has the advantage of dividing the efforts to be made, and therefore the means to be implemented, into four categories : a sober lifestyle ; an improvement in the energy efficiency of equipment; the change of energy system by substituting renewable energy for fossil fuels ; industrial manufacturing processes, their carbon content and carbon sequestration, notably through the evolution of agricultural models. Four pillars of any energy policy, he said, four pillars like a table. Nevertheless, he insisted above all on the upstream: that each actor, starting with the citizens themselves, have the necessary information to truly understand the issues.

-

Édouard Bouin developed the theses of Agir pour le climat : the urgency of mobilising massive financial resources on a European scale to meet the climate challenge. The slogan of his association is: « if the climate were a bank… ": during the 2008 financial crisis, a thousand billion were invested by the European Union to save the banks, let’s put the same amounts for the climate. As regards the actions to be taken, he stressed the importance of having a dedicated financial tool, the European Climate Bank, to organise a set of direct green investment policies, loans, subsidies and support for more sober lifestyles.

-

Anne Rostaing presented the original experience of the Coopérative Carbone de la Rochelle, a tool for mobilising all actors around common projects.

-

Denis Bonnel underlined the importance of initial public investments to achieve technological breakthroughs and massive industrialisation of processes that allow electricity production by photovoltaic panels to compete victoriously with the use of fossil energy.

-

Alexis Normand showed the possibility of mobilising digital tools to enable everyone to be aware of their own carbon footprint.

A/ Capping and performance requirements

How can we achieve a year-by-year performance obligation based on reducing the footprint at a fixed rate?

In this family of policies, the question of the obligation of result has in fact rarely been asked for three reasons :

-

the scenarios are often established with a rather distant horizon (ten to thirty years) ;

-

the diversity of sectoral policies rarely allows their effects to be added up ;

-

the evolution of the different actors, the citizens themselves, the companies, the banks, the territories, is considered in parallel, so that the idea of an overall ceiling, and therefore of rationing, of the quantity of fossil energy used in total is in a way outside the scope of the reasoning.

Even Édouard Bouin, who places the greatest emphasis on the importance of the financial means to be mobilised, recognises that the central question is the efficiency of the different modes of investment and not their amount.

Even if the obligations of result that the European Union has set itself are distant objectives, Antoine Colombani tells us that the European Commission is, this time, determined to set a trajectory for the various Member States, with a progress report every two years and the desire, in the image of what happens in other areas, public deficits or human rights, to take graduated initiatives with regard to States that do not respect the trajectory : recommendations ; litigation before the Court of Justice.

It also recalls that the European Union, because of its competence over the single market, has direct levers to maintain this trajectory, with the ETS system, carbon adjustments at borders and the development of a European regulatory framework to move towards sustainable products : repairable, reusable, recyclable, in accordance with the precepts of the circular economy, and low-carbon for both their production and their use.

How can we avoid every measure envisaged being distorted by lobbies ?

This point was not really discussed during the session. It is nevertheless crucial, as shown by the previous sessions which cited the maintenance of free quotas for certain economic activities exposed to international competition in the case of the ETS, or the absence of in-depth reform of agriculture, whose current emissions play a large role in GHG emissions.

Antoine Colombani recalled the scale of the recovery plan adopted by the European Union. It is a major tool for financing the transition. It is planned that 37 % of national recovery plans will go to the transition and that the rest of the investments must not harm it. (In the past, public action has often been schizophrenic, supporting the transition with one hand and the use of fossil fuels with the other, to the extent that since the 1992 Earth Summit the international community has not really succeeded in limiting subsidies to fossil fuels, which for a long time outweighed the funding invested in combating them.)

Philippe Quirion nevertheless points out the two limitations of this approach to the recovery plan. First of all, it is not easy, in his opinion, to avoid the fact that in the European and national recovery plans, governments are smearing « green paint » on investments that are in fact aimed at other objectives. This is all the more true given that after the pandemic, governments will be under emergency pressure. Secondly, public aid and subsidies do not help to support the most virtuous actions: it is difficult, he says, to subsidise sobriety! And the same problem arises with the ETS: we certainly penalise the most emitting factories but to subsidise the least emitting ones : rather than encouraging cement factories to improve their energy efficiency, should we not rather encourage them to use less cement ?

This brings us back to the debate of the fifth session on the limits of actions aimed at companies : they can, of course, to take up the four pillars of NegaWatt, improve their performance, and possibly « change fuel » by switching from fossil fuels to renewable energies, but they are unable to bring about radical transformations of the economic system, which Christian Gollier reminded us in the third session were inevitable. As a result, they remain, as the fifth session illustrated, on the surface of things, not to mention the ability of industrial lobbies to invoke international competitiveness to avoid measures that are too restrictive towards them.

How to guarantee the continuity of the process beyond political changes?

Benoît Lebot pointed out that for the past thirty years there has been nothing but « stop and go ». It was clear from the previous sessions that, unless there are real transparent pacts (Bettina Laville spoke of two five-year periods), this stop-and-go approach is likely to continue with this family of solutions.

The European Union’s firm commitment to an annual trajectory and the multi-annual nature of European budgets and commitments may indeed provide an element of response, as European commitments cushion, to a certain extent, the political fluctuations of each Member State. However, this trajectory would have to be a real legal obligation engaging the responsibility of the leaders. We return to the debate of the second session: « who is responsible for what » and the need to move towards a European Charter of Responsibilities that complements the Convention on Human Rights.

What can be the role of technical innovations? Can they disrupt the strategy of the actors }}

Denis Bonnelle shows the need to open the way to what the historian of science and technology Bertrand Gille called the « change of technical system » by developing two major ideas : ltechnologies do not develop independently of each other but form at any moment in history a coherent and interrelated system; and there comes a time when societies are faced with a blocked technical system, imposing a « systemic » break.

Can we consider the current technical system, based since the industrial revolution on the substitution of fossil energy for human and animal energy, as such a blocked system, and under what conditions, particularly in terms of public action, can we rapidly switch to another technical system? This is what Denis Bonnelle mentions in connection with the production of renewable electrical energy, through solar energy, thanks to photovoltaic solar panels.

He points out that any change in technical system begins with a vicious circle: in the absence of significant markets, we are left with costly prototypes that are supported at arm’s length by the public authorities and, as they are costly, no market opens up that would allow economies of scale. In order to move from a vicious circle to a virtuous spiral in which lower costs give rise to an increasingly large market, which in turn contributes to making the new technique increasingly competitive, initial public aid is needed, as the ‘price signal’ is not enough. This shift, he says, was made possible by the German government’s promotion of electricity production using solar panels. The German government has invested massively to create the market for these panels. It made a double sacrifice, financial on the one hand, to get the system off the ground, and industrial on the other, since the German photovoltaic industry was sacrificed in favour of the Chinese industry, which was more capable of changing scale. But, says Denis Bonnelle, we are now reaching a stage where the projects are becoming profitable, outperforming fossil fuel power generation projects. In doing so, he says, the German government has created a true global public good.

He also reminds us that in order to switch to a new technical system, a coherent attitude is needed : as is well known, the production of electrical energy by wind and sun is by nature intermittent. It is therefore necessary to accept, on the one hand, to develop around this renewable energy a real technical system, in particular with the production of green hydrogen used as a fuel instead of traditional energies and, on the other hand, to admit the development of a network of high voltage lines to ensure the north-south (for wind energy) and south-north (for solar energy) transfers.

Alexis Normand presented additional thoughts on the evolution induced by the digital revolution. He cited the application of « open banking » techniques to the traceability of carbon emissions. This concept according to Wikipedia describes « a banking system in which consumers and businesses can allow banks or third-party financial service providers to access data about their assets and financial transactions through secure online channels ". Open banking itself is an application of the more general concept of open innovation, also known as « distributed innovation », which, according to Wikipedia, « refers to modes of innovation in research and development based on sharing and collaboration between stakeholders ».

In this way, a convergence around a new technical system can take place around the fight against global warming, both on the energy production side and on the emissions traceability side. Attention to this emergence and the creation of its conditions does not imply « technological romanticism ». Denis Péchin reminded us that a true energy balance of photovoltaics must be made and all the costs integrated to ensure that the imported emissions linked to the implementation of the entire system, production of the panels, installation, and the networks linked to it do not ultimately represent fossil energy costs that reduce its interest. Denis Bonnelle responds to this by setting up a coherent technical system : in the past, it took eight years of electrical energy production by the panels, over their thirty-year lifespan, to cover the energy required to produce and install them. With economies of scale, this payback time has now been reduced to an average of two years : 28 years of available energy. Moreover, unlike batteries, photovoltaic panels do not use rare earths but silicon, one of the most abundant materials in nature. The production technology refers to other technical innovations such as the production of extremely pure silicon and the ability to create thin wafers of material that are found in computer technology. These interdependent developments are characteristic of the emergence of a new technical system.

And as far as batteries are concerned, Antoine Colombani recalls the interest of the regulatory action which, at European level, aims today to impose recycling, to develop performance and to set a ceiling on emissions for the entire life cycle of batteries.

At what policy scale is the system relevant?

In an article published in the newspaper Les Echos on 17 March 2021, Christian de Perthuis, extending a reflection carried out within the Assises, evokes the need for a « double rationing » to achieve the obligation of result: a rationing of supply, acting directly on the emissions of the system of production of goods and services and a rationing of demand to which we will return later.

Antoine Colombani has clearly illustrated the fact that the European Union is today the right scale to move towards a rationing of supply and a transformation of technical systems, by combining emission quotas for companies, public investments to develop a new technical system and regulations to impose a complete approach to the life cycle of products. On the other hand, member countries would be better equipped, within the framework of general principles set at EU level, to act on the rationing of demand and, through the tax system, to ensure a fair distribution of efforts among citizens, thus enabling a shift towards an economy and lifestyles that respect the limits of the planet.

Finally, as mentioned below, the territories have a decisive role to play. The fight against global warming is therefore sketching out the principles of a multi-level governance that would find immediate application in the concrete implementation of European and national recovery plans.

After 30 years of trial and error, is this second family of solutions likely to be able to rise to the challenge?

No convincing answer was given during the session to this fundamental question. In the light of the above, the European commitment on the one hand and the chances of a technical system tipping over on the other, we could nonetheless be on the verge, if not of a real obligation of result, about which Philippe Quirion expressed some doubts, then at least of a greater coherence between the stated objectives and the actions put in place.

Joining by another end what Édouard Bouin said in the prologue « if the climate were a bank it would already be saved ", Philippe Quirion points out that between 1942 and 1944 the United States was able to completely reconvert its industry to win the war. « It is necessary, he says, to do the same thing today to win the climate war but, he reminds us, there is no technical alternative on certain points and it will necessarily be necessary to go towards sobriety ". The ecology of the 1960s (implicitly referring to the Meadows report for the Club of Rome, « the limits to growth ") placed too much emphasis on the scarcity of resources. We now realise that this scarcity is a second-order problem, the central problem, illustrated by greenhouse gas emissions, is that of waste, not resources.

B/ Total footprint of societies

The debate here has focused on three points :

-

does the carbon footprint of societies better reflect our collective responsibility for the climate than « territorial emissions "?

-

should the footprint focus on carbon dioxide emissions or should the analysis be extended to other greenhouse gases, in particular methane and nitrous oxide?

-

Do the current approaches of the second family of solutions allow for the traceability of emissions throughout the value chain?

The responsibility of our societies towards the climate

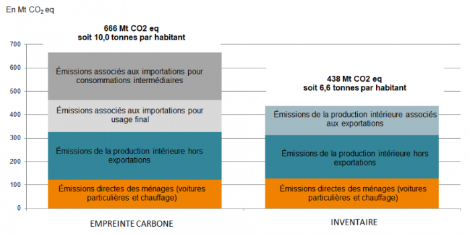

The total carbon footprint associated with our consumption is the most direct expression of our lifestyle. The graph below, taken from the most recent report of the Ministry of Ecological Transition, reminds us of the essential data to bear in mind : the emissions on national soil associated with our lifestyle represent just over 300 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, whereas our total footprint is 666 million.

Guy Kulitza of the Citizens’ Climate Convention notes that direct household emissions, mainly from heating and cars, which are often the focus of attention, account for less than 20 % of our total carbon footprint.

Philippe Quirion believes that even this footprint does not fully reflect our responsibility : it also concerns emissions from domestic production associated with exports - adopting a double standard with fossil fuel efficient production systems for domestic consumption and less efficient systems for exports would indeed be irresponsible - and our investments abroad. On the last point, he cites the example of the Chinese government, which is massively financing the construction of coal-fired power plants in third countries. An overall examination of the responsibility of European society, with a view to a European law of responsibility, should naturally take into account these two elements.

Is it enough to focus on the carbon footprint, or should we not take into account the other greenhouse gases?

Benoît Lebot reminds us that the other greenhouse gases, essentially methane and nitrous oxide, together represent 30 % of the greenhouse effect in terms of impact on the climate. Both are directly associated with our agricultural model. It therefore seems inevitable to ensure their traceability in the same way as carbon dioxide.

Are we giving ourselves the means to trace carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide emissions throughout the production chain?

The discussion in the first session provided an opportunity to comment on the above graph. In the 54 % of the total footprint associated with « imports » of greenhouse gases, there are two unequal shares : a minority results from emissions associated with imports for final use, a majority is attributable to imports for intermediate consumption, thus transiting through our own production apparatus. The means of traceability depend on these two categories.

Benoît Lebot insisted on the importance in this field of the precise knowledge to be mobilised or built up and of strengthening the human resources devoted to this knowledge, without which, for example for the EU-ETS, we will not have carbon accounting worthy of the name and certification. It is true that the current evaluation of the footprint, both at European and French level, is based, as Christian De Perthuis pointed out at a previous meeting, on a flat-rate evaluation, a « benchmark », and not on the actual evaluation of the emissions imported into the various sectors, which constitutes, particularly in the hypothesis of a carbon adjustment at the borders, a premium for the least efficient systems.

Before we even ask ourselves the question of the traceability of imported emissions, says Benoît Lebot, we need to strengthen our accounting of the carbon equivalents of the various greenhouse gases. Yes, he says, traceability is possible, but let’s already have the means to know the fundamentals. He cites a recent report on American cities that tried to have a complete approach to their emissions and concluded that official emissions were underestimated by at least 20 %2 : « of course, there is the invisible part of imported greenhouse gases, but there are even errors on direct emissions ".

While acknowledging that the European Union has not yet taken the measure of this issue of traceability of greenhouse gas emissions throughout the supply chain, Antoine Colombani reminds us that the Commission is in the process of taking the issue seriously : in the wake of the European transposition of the French law on duty of care, it is working on a revision of the extra-financial reporting obligations of companies, with the obligation to report on the activity of subcontractors and suppliers, and on product labelling (in the direction of a carbo score) ; a legislative project on the consideration of imported deforestation is also on the table (a long-standing demand of civil society concerning, in particular, the import of palm oil, soya and beef, which contribute significantly to deforestation) ; finally, this issue will be at the heart of carbon adjustment at borders.

For his part, Alexis Normand says that not only traceability is vital but it is also within reach. Referring to the aforementioned open banking movement, he believes that this traceability can be directly inspired by that of health data. Greenly has already developed an application on bank accounts that would make it possible to deduce from physical transactions the amount of carbon consumed by each person. This would have two applications : firstly, to inform consumers ; secondly, in terms of accounting, to convert the « ledgers » of companies into a carbon balance sheet.

This is, he acknowledges, only a starting point because, as with the general assessment of the footprint, the calculation is based on average data on imported emissions incorporated into products. According to him, and here we return to Alexandre Rambaud’s reflections in session 5, financial accounting and carbon accounting will gradually merge and chartered accountants will have to certify the carbon account in the same way as they certify financial statements today. This movement will be supported in particular by financial portfolio managers who, for their part, are confronted with the TCFD (Task Force on Climate Related Finance Disclosure), resulting from the Paris Agreements, with the obligation to evaluate the risk of their portfolio to climate hazards.

C/ Social justice and decoupling

During the session, it was mainly the issue of demand rationing that was debated.

This issue was introduced by Benoît Lebot, who stressed that sobriety was the most important of the four pillars of the NegaWatt scenarios. Raymond Zaharia associated the idea of decoupling with the idea of « just need ». Without demand control, he said, we will achieve nothing and this control cannot be achieved without the commitment of public power. However, he says, it is today totally absent from what must be considered as a misuse of technological capacities. He takes the example of the new smartphones which offer image accuracy that bears no relation to actual needs. Capping demand is also simply a way of combating hubris, the excessiveness of our formulation of needs. He took the example of Tesla and its project to launch thousands of satellites into space to improve the Internet: what he called an « Internet of the fishes » because most of this coverage would actually be in the ocean.

Philippe Quirion welcomed the statement of the question : the decoupling in question is not the decoupling of GDP from fossil energy consumption, but the decoupling of well-being. He refers in particular to an article published recently by the journal Global Environmental Change, in November 2020. It is entitled: « Offering a decent lifestyle to all with a minimum of energy : a global scenario ". This article underlines, after many others, that beyond a certain level of material resources, there is a real decoupling between a sense of well-being and consumption. The authors are interested in the following question : is it conceivable to ensure the well-being of all, while drastically reducing (95% in developed countries, 60% on average) energy consumption ? To do this, they start from the observation that basic needs are very comparable from one country to another but that, on the other hand, the cultural (and consumption) models for satisfying these basic needs are radically different from one country to another. According to them, yes, it is possible to satisfy everyone’s well-being, but only by breaking with the marginalist approach used until now and by combining the efficiency of new technologies with radical transformations on the demand side.

For Murielle Raulic of the Citizens’ Climate Convention, by focusing on on direct consumption by citizens, which accounts for less than 20% of greenhouse gas emissions, we are pointing the finger at the poorest and missing the central issue of decoupling. And Guy Kulitza specifies the reflections of the Citizens’ Convention: « sobriety is not just a sacrifice ". Like the extras we do at Christmas and New Year’s Day, as opposed to everyday consumption such as that caused by nitrogen fertilisers: « Well-being means having what you need at a time when you need it and not everything right away ". Hence, he says, the opposition to advertising in the citizens’ report.

For his part, Samuel Thirion wonders whether sobriety should not be an obligation ? Shouldn’t « superfluous needs » not exceed a certain threshold? Benoît Lebot believes that it is possible to make sobriety a public policy provided that it is first recognised by all as part of the solution. According to him, the obligation of result should be broken down into an obligation of result for each of the four pillars of the NegaWatt scenario.

As we can see, the debate on capping demand has thus been initiated.

D/ Mobilising all the players

This question was broken down into two parts: is the proposed change physically possible ? And how can all the actors be involved ?

On the first point, we will not go back to the answers already given : the NegaWatt type scenarios illustrate the technical possibility of respecting an obligation of result and even make it possible, to a certain extent, to break down this obligation of result between the four pillars. Similarly, the article cited by Philippe Quirion shows that it is already possible, independently of the technological changes described above, to satisfy the essential needs of all (until the 18th century, this was the very definition of the oeconomy).

On the second point, two ideas of a different nature were developed. Firstly, with regard to the mobilisation of citizens, both Benoît Lebot and Charles Hayek, an engineer and mayor of a small commune in Franche Comté, emphasise the need to give them simple and clear means to understand and act. Benoît Lebot returned to the question of human resources: « the banks say that there is no demand for emission reduction but, he said, this is because there is no funding for diagnosis to determine the potential for reduction and no human capacity available, starting at the local level ". And Charles Hayek observes: « I talk to citizens. The big radio stations are talking nonsense. People are no longer interested in these issues because they are not given any concrete explanation. It is not by taxing petrol and fuel oil that they will be interested, but by proposing credible and honest solutions ! ".

This need for a simple and readable mechanism seems to be a priority today. This brings us back to the central role of territories, as explained by Anne Rostaing based on the experience of the Coopérative Carbone de la Rochelle . This Carbon Cooperative is an original tool, in the form of an SCIC, associating local authorities, companies and universities and aiming to support the territorial action of different types of actors, to pool knowledge at the scale of a territory and to organise the financing of projects : it is not, she says, strictly speaking, an obligation of result, but a way of organising territorial action, to provide a tool at the service of all local actors. Because, she says, « while we suffer from a lot of imprecision on the global impacts, we can on the other hand evaluate each local project ". Without a territorial systemic approach, she adds, there will always be rebound effects. The advantage of the territorial level is that all areas of life in the territory are concerned, including, for example, carbon sequestration through changes in agriculture. To enable the decoupling we have talked about, to highlight the essential role of cities, we must enable everyone to know the source of what they consume, develop tools enabling each territory to take responsibility and, to do this, increase the capacity of each actor to act at his or her level. However, the regulatory framework should not be a barrier, and we should be able to act with fewer barriers than today: « we notice that citizens are aware and that when we offer them tools to act they want to be actors and are ready to act ". She cites the example of self-consumption of electricity in a neighbourhood, which can also lead to the production of hydrogen, provided the regulatory framework allows it. According to her, at the territorial level, voluntarism and the demonstration effect are two essential levers.

We therefore find here the central role of the territories and the already mentioned question of the articulation of the three levels Europe, Nations, Territories which will be the subject of session 8.

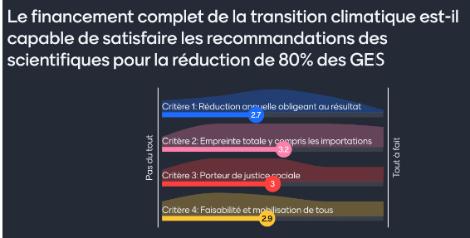

In conclusion, we can consider that the speakers were able to shed valuable light on each of the questions raised. Do these perspectives allow this family of solutions to rise to the challenge? The online survey organised at the end of the session offers a mixed picture :

-

performance obligation ? 2.8 out of 5

-

total footprint ? 3.2 out of 5

-

social justice and decoupling ? 3 out of 5

-

mobilisation of all actors ? 2.9 out of 5

This survey has no scientific value, of course, but it gives the temperature of the reactions.

1 Recall :

-

Family 1 : the price signal. Gradually reduce demand by setting a higher and higher price per ton of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere and redistributing, in a way to be defined, the revenues derived from the high carbon price, so as to respect a principle of social justice.

-

Family 2 : the combination of sectoral policies aimed at defining reductions in the carbon footprint in all areas by setting quantified targets for each of them and implementing bans, obligations, incentives, public investments, technical innovations and taxation to achieve them.

-

Family 3 : allocation of quotas. Allocate the total footprint between actors according to a predefined key. This is the most direct management of rationing. This family can be broken down into two very different sub-families :

-

family 3.1. : quotas are allocated to sectors of activity and companies ;

-

family 3.2: quotas are allocated to people who are considered the final beneficiaries and clients of economic activity and of the activity of administrations.

-

2 Nature journal, published February 2021 : « The underestimation of greenhouse gas emissions in US cities » - htpps://www.nature.com/article/s41467-020-20871-0).

Références

-

One of Benoit Lebot’s contributions : Concerning the new study on the difference between GHG measurement and estimation, download the pdf under_reporting_of_greenhouse_gas_emissions_in_us_cities.pdf or on the « nature communications » website Under-reporting of greenhouse gas emissions in U.S. cities

-

Edouard Bouin distributed the short slide show si le climat était une banque…pdf

-

Anne Rostaing for the Coopérative Carbone (La Rochelle) gave examples of their actions : Example 1 : We work on sobriety : we accompany citizens to CONCRETE their actions to change mobility, and we evaluate and accompany alternative offers. Example 2 : we develop actions of collective self-consumption of renewable energy at the neighbourhood level. Example 3 : a territorial circular economy approach. Example 4 : sequestration : private individuals are carrying out tree planting projects, we are planting in the Marais Poitevin and working on C sequestration in the soil. And finally, research work on C capture in our wetlands.

-

One of Philippe Quirion’s contributions (RAC): An article that quantifies the energy needed for everyone on the planet to have a decent life.pdf

En savoir plus

Anyone can draw on the open resources of the conference to develop publications or viewpoints. Please cite the contribution of the Climate Conferences.

Nine two-hour sessions are posted in full on the facebook of the climate conference