The climate conference - Obligation of results and carbon footprint of French society

Magnitude, uncertainties, measurement tools (session 1)

Jean Jouzel, Christian de Perthuis, Corinne Le Quéré, Arnaud Leroy, Jérôme Boutang, Pierre Calame, février 2021

In the face of global warming, how can we move towards an obligation of result? This is what is at stake in this series of public debates, which will familiarise the public with the idea of an obligation to achieve results, explore the various possible ways of meeting this obligation and challenge the public authorities on how to assume their responsibilities in this respect.

Mitigation targets are currently defined in terms of territorial emissions, calculated from national inventories. These inventories, harmonised using methodologies validated by the IPCC, are subject to verification by the United Nations. The national inventories do not take into account the emissions incorporated in imported goods and services, nor those resulting from the use of exported goods. Taking these indirect emissions into account makes it possible to calculate « carbon footprints ». The first session is devoted to the study of these metrics by seeking to shed light on three questions :

-

What is the degree of correlation or decorrelation between the carbon footprint and territorial emissions ?

-

Should the inventory metric be completed by the footprint metric ?

-

If so, how should the relative weight of the two indicators be weighted in the definition and monitoring of mitigation objectives ?

À télécharger : expose_jerome_boutang_inventaire_citepa_empreinte.pdf (830 Kio), expose_corinne_le_quere_maitriser_empreinte_carbone_de_la_france_assises-1.pdf (720 Kio)

The first session of the Assises du climat brought together the best French experts in the field of greenhouse gas emissions measurement: Jean Jouzel, former vice-president of the IPCC, Christian De Perthuis, founder of the Climate Economics Chair, Corine Le Quéré, president of the High Council for the Climate, Arnaud Leroy, president of ADEME, Jérôme Boutang, director of Citepa. In an hour and a half, these experts helped to frame the issues.

1. The consumption footprint of French society, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, is undoubtedly the expression of the impact of our way of life on the biosphere and the climate. It is therefore this impact and its reduction by 2050 that constitutes our obligation of result.

2. According to the figures of the High Climate Council, to assume our share of responsibility by 2050 in order to meet the objective of a 1.5° increase in average global temperatures, we must, according to Corinne Le Quéré, reduce this footprint by 80 % by 2050. This means, by adopting a geometric sequence corresponding to a constant annual percentage reduction, a reduction of 5% per year. This is the framework for reflection that we can adopt for our conference.

3. Compared to what has happened since 1995, this rate of reduction constitutes a radical break. Indeed, as the graphs drawn up by the High Council for the Climate show, from 1995 to 2015 the total carbon footprint of French society hardly decreased at all, the reduction of « territorial » emissions on national soil being more than offset by the growth of « imported » emissions due to our consumption patterns.

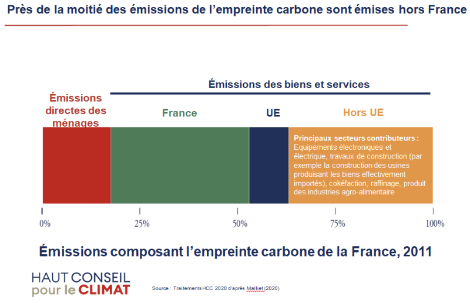

4. More precisely (see graph 1), of the 749 million tonnes of CO2 emitted by French society in 2018, i.e. 11.5 tonnes of CO2 per inhabitant, direct household emissions (heating, petrol for the car, etc.), which are the most visible and often monopolise attention, only represent 16% in reality, the rest being linked to domestic production and, above all, for 429 million tonnes out of the total of 749 to imports.

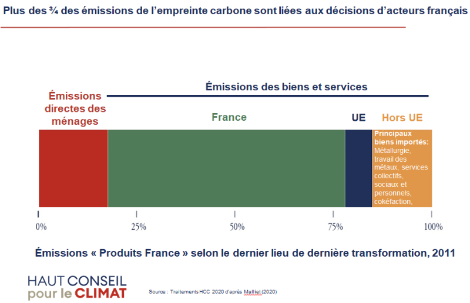

5. A more detailed analysis of the nature of these imports shows that for the most part they are intermediate goods that are part of the French production system (see graph 2). This means that the management by French companies of the production chain over which they have a large degree of control, through the choice of suppliers and subcontractors, constitutes a major lever for transformation, provided that these companies gradually assume their responsibilities by imposing « carbon traceability » on the entire chain. And this traceability should include imported deforestation in the carbon balance of the sector.

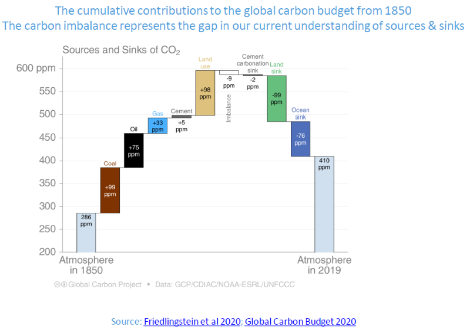

6. As the important 2020 international report « Global Carbon Project » reminds us, since 1950, CO2 emissions from land-use change, mainly deforestation and loss of land-use richness, has just been balanced by the increase in CO2 uptake by the biosphere (see charts 3 and 4). To give an order of magnitude, in 2019, globally, 34 gigatonnes of CO2 result from fossil energy consumption, and 6 from land use change.

What are these calculations worth? Current inaccuracy of tools for measuring the carbon footprint of French society

1. As Christian De Perthuis and Jérôme Boutang have pointed out, all international negotiations on global warming to date have focused on territorial emissions, on national soil, and not on the carbon footprint of companies. This is the effect of the obsession with sovereignty : instead of considering that companies are responsible for their carbon footprint, they stick to the emissions of each country on its national soil. In principle, these emissions are measured according to an international protocol defined by the IPCC for the United Nations, without the international community really having the means to check how this protocol is applied in each country. In France, emissions from households, companies and administrations are measured according to this protocol, which only imperfectly takes into account changes in land use.

An important note to avoid erroneous conclusions : when national emissions are measured, the emissions of households are added together, without taking into account the energy incorporated in the goods and services they purchase, the emissions of companies and of the entire economic system, whether it be production for French households or production for export, and the emissions of government agencies. In contrast, when we look at the total carbon footprint, associated with the lifestyle of French society, we measure the footprint per capita and it includes both the emissions of companies destined for the French market and all imports of goods and services, either in the form of finished products directly purchased by French households or, which constitutes the bulk - 60% of the total footprint - of intermediate goods and services processed by French companies.

2. As a result of the prominence given in international negotiations to « territorial » emissions and the absence of direct measurements of the carbon balance in international production chains, the current measurement of society’s carbon footprint, and a fortiori of other greenhouse gases, is much more approximate than the measurement of territorial emissions. Jérôme Boutang estimates that the uncertainty on territorial emissions is +/- 11%. On the other hand, the uncertainty on the comparisons of these emissions from one year to another is only +/- 2%. This makes the inter-annual evolution of the territorial footprint a reliable measure.

3. The assessment of society’s carbon footprint is indirect. It is deduced from the knowledge of trade flows between the various economic sectors available in the national accounts. The same tables are used from one year to the next and the latest tables date from 2016. For the carbon footprint and even more so for the footprint related to the emissions of the 7 greenhouse gases, it can be considered as a good order of magnitude.

4. To directly analyse the carbon footprint of the various production sectors, so as to have a more tangible knowledge of the consequences of our way of life, the most precise source today is provided by ADEME (site www.base-impact.ademe.fr) which details this footprint for several hundred industrial sectors. It is on this basis that we can envisage raising society’s awareness of the impact of its consumption patterns, with the display of an eco score for each product. Nevertheless, this assessment of the carbon footprints of the sectors remains incomplete, generally stopping at the direct subcontractors of companies without taking into account the long chain of subcontractors and suppliers that characterise today’s global production systems.

5. There are certainly Life Cycle Analyses (LCA) of products, but according to Arnaud Leroy, these LCAs, by limiting themselves to carbon, favour the large American and Brazilian agri-food producers whose negative impacts on biodiversity, water and the dissemination of chemical inputs are not taken into account.

6. Another consequence of the « fixed » measurement of the carbon footprint based on national accounting tables is, according to Jérôme Boutang, a methodology that is too global to evaluate the border adjustment tax, as the European Union would like: it is easy to understand why this method of calculation gives averages and does not allow us to penalise the companies with the worst carbon footprints within each production sector, which is the essential objective.

7. Arnaud Leroy also stresses the importance of a serious measurement of the carbon traceability of production chains and, more generally, of the seriousness of life cycle analyses: the greater the challenge of reducing the annual footprint ceiling, the greater the temptation for certain States to minimise emissions in the part of the production chain that they control, creating a distortion of competition.

The interaction between the way the performance obligation is managed and the actual traceability of the footprint

As we have just seen, there has so far been a strong interaction between the sovereignty of States and the nature of the measurement used in international negotiations, favouring the measurement of territorial emissions to the detriment of the carbon footprint of the lifestyle. In other words, making the carbon footprint the focus of performance obligations today has the consequence of determining the conditions for traceability of emissions along the entire chain. In this respect, we can think of the « motorway ticket » method: the person who has lost his ticket pays the maximum distance; here, when the sectors are not able to impose traceability rules on all suppliers and subcontractors, the highest value of carbon emissions is always adopted.

Références

-

Presentation by Christian de Perthuis : The three thermometers of climate action, instructions for use

-

Presentation by Jérôme Boutang : National emission inventories versus consumption footprint

-

Presentation by Corinne Le Quéré : How to integrate indirect emissions into climate targets