The circular economy, a model for the ecological transition

Bulletin n°115

mai 2022

« AdP - Villes en Développement » is a forum for exchange and reflection on urban development and city management in emerging countries. AdP brings together urban planners, engineers, architects, economists, geographers, sociologists, etc. who work independently or in public services and consultancy firms, and who have an entirely or alternately international career. « AdP - Villes en Développement » is the editor-in-chief of the « Villes en Développement » Bulletin from which this article is taken.

Within the framework of partnerships, ADP Villes en Développement opens its newsletter to the French Development Agency. AFD publishes below a text co-authored by Hassan Mouatadid, Deputy Head of its Urban Development, Housing and Planning Division, with Jonas Byström, Senior Engineer in the Circular Economy Division of the European Investment Bank (EIB) and Philippe Masset, Director of Europe and International of ADEME, the French Agency for the Ecological Transition.

À télécharger : bulletin-115-fr.pdf (3,7 Mio)

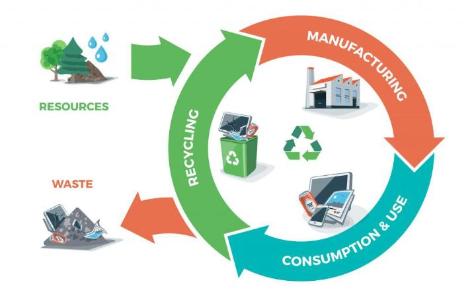

Faced with the scarcity of natural resources and the imperative of ecological transition, the concept of the circular economy is gradually gaining ground. It is becoming a new development model that breaks with the traditional linear model of « extract, manufacture, consume, throw away », in favour of a loop logic. The objective is to aim for a sober and efficient management of resources to limit environmental impacts.

The circular economy, a necessity

In 2020, a report by the International Resource Panel (IRP) 1 predicted a gradual doubling of demand for natural resources (excluding water) by 2060 2, to 19 t/inhab/yr. Most of the increase would concern construction and industrial materials. In view of this, a change of model seems essential.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) indicated in 2011 that a sustainable linear system would require individual consumption to be limited to 3 - 6 t/inhab/yr by 2060, which seems unimaginable economically. The UN therefore advocated working more on the « efficient » use of resources.

The extraction and processing of materials and fuels account for 53% of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Experts say that the growth in demand for raw materials by 2060 will contribute to a 43% increase in GHG emissions 3. Resource extraction and processing is also responsible for 90% of the world’s biodiversity and water losses.

The circular economy, towards a reality

While the European Union defines the circular economy as « a production and consumption model that consists of sharing, reusing, repairing, renovating and recycling existing products and materials for as long as possible so that they retain their value » 4, ADEME specifies that its application contributes to « reducing the impact on the environment, while developing the well-being of individuals » 5. The agency distinguishes seven pillars of action grouped into three areas, where the whole forms a cycle, and each step leads to the next 6.

Sustainable procurement emphasises the producers’ duty to look at the materials they use. For example, the digital application Phenix combats food waste by reselling unsold products.

Ecodesign means proposing products, services or processes, taking into account their impact, from their creation to their elimination. For example, CINE manufactures a household cleaner that contains fewer ecotoxic substances and is more biodegradable.

Industrial and territorial ecology creates chains of interdependence between economic production entities to optimise resource flows. For example, the « eco-network » of Biotop companies as well as 162 other public and private partners pool their needs and waste, in particular by recovering PVC scraps or coffee bags or by reusing big bags.

The functionality economy favours the sale of a service or the rental of a maintained product rather than the sale of a product as such. The customer can thus benefit from an asset without owning it. For example, Forézienne MFLS manufactures cutting tools for mechanical woodworking and rents and maintains its equipment. To be economically viable, the longevity of the equipment has been increased by 20%.

Responsible consumption commits each individual to make consumption choices by integrating the life cycle of goods and services. For example, evaluating and comparing according to labels and indices; favouring products with a longer life, even if they are more expensive, are among the main principles.

Extending the life span of products encourages the use of repair, donation or sale instead of throwing them away. For example, Envie recovers paramedical equipment to repair it and give it away or sell it at a low price to people in difficulty.

Recycling should only take place on the non-reusable part of the material. Although this is the pillar most often considered, it should be the last link in the chain to optimise the impacts of the circular model.

The circular economy and the sustainable city

The circular economy appears in several respects to be a relevant and coherent approach to the challenges of the « sustainable city ». It is at the heart of the urban development intervention strategy of international financial institutions, including the AFD and the EIB.

The circular economy is an essential response to the significant growth in global resource consumption, 70% of which is consumed in and by cities. Moreover, cities can be the cradle for the development of circular models. By 2030, 60% of the world’s population will live in cities. And increasing urbanisation should facilitate the development of these models.

Therefore, the circular economy plays a new role in waste management and recycling, by seeking resource efficiency: extending the life of products, giving them a second life, optimising the use of raw materials, etc. This approach makes it possible to limit the production of waste and to improve the quality of life. This approach makes it possible to limit the production of waste and to optimise its management, which weighs heavily on the budgets of local authorities, particularly in developing countries.

Factors for change

The issues and factors contributing to the implementation of a circular economy are technical, political, economic, sociological and human. Sociological and human factors are the most complex to activate. They require imagining different habits without the consumer or producer considering that this is a regression. It is much more a question of accepting individual limitations in favour of a collective, of redefining one’s needs, of adapting one’s consumption accordingly and of no longer linking consumption and ownership.

This complex paradigm requires a review of the ways of doing, producing and acting at several levels in favour of the environmental, economic and social commons. Common values are thus destined to evolve and this implies major changes in the world of work. Accompanying change and raising the awareness of decision-makers, producers, sellers and consumers is therefore becoming a key element in the appropriation of this new framework.

-

1 IPCC equivalent for raw materials www.resourcepanel.org/

-

2 80 billion tonnes in 2015 to 180/190 billion tonnes in 2060, and from 12 t/inhab/yr to 19 t/inhab/yr

-

3 World Resources Outlook, UN Environment, 2019

-

4 Circular economy: definition, importance and benefits | News | European Parliament (europa.eu)

-

5 Circular economy - Sustainable consumption - ADEME