Preservation of a Hundred-year-old Wooden District Through Sustainable Regeneration

The case of Supilinn in Tartu

Katalin Fehér, 2016

Supilinn is a historical neighbourhood of Tartu, part of the wooden heritage of the Baltic region. There were no urban renewal activities for several decades, but now the neighbourhood has begun to be gentrified. A relatively rare feature in East Central European countries, an entirely bottom-up civil movement was born in reaction. The movement aimed to slow gentrification and generate sustainable development of the area.

General data:

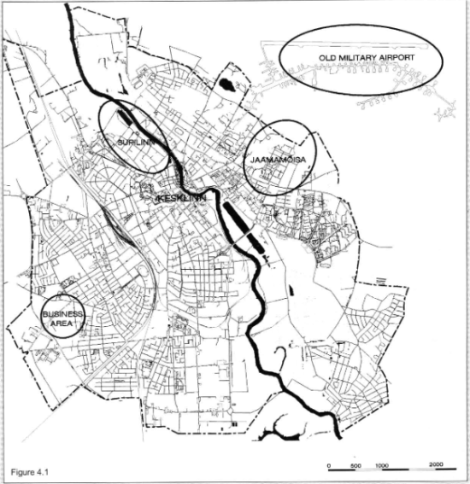

Tartu is the second largest city of Estonia. It is located in the centre of south Estonia, on the banks of the river Emajogi which connects the two main lakes of the country.

Population: 97,117 (2013) - Generally, the population is decreasing. (Statistics Stonia, 2014)

Supilinn: 1860 inhabitants (2013), 43 ha

Renewal of the old wooden district of Supilinn, located in the city of Tartu, has been expressed as a political intention for a long time without taking place in reality. However this situation seems to have changed in recent times. During the last decade gentrification of the formerly run-down neighbourhood has started. Inhabitants of Supilinn organized themselves in order to put pressure on the local government to slow down renewal and gentrification. Due to this bottom-up movement, a gentle and sustainable regeneration has been conducted until the present. This movement is an important example for bottom-up organisation of urban renewal that has few precedents in East-Central Europe and more specifically in the Baltic region.

Supilinn, the old wooden district of Tartu

The neighbourhood of Supilinn, which can be translated into English as ‘Soup Town’ is one of the smallest districts of Tartu. The area is located close to the city centre, near the original medieval wall of the mercantile town. The eastern border of the area is the Emajogi River, while the northern border is shared with an inbuilt open space which is now a recreational park.

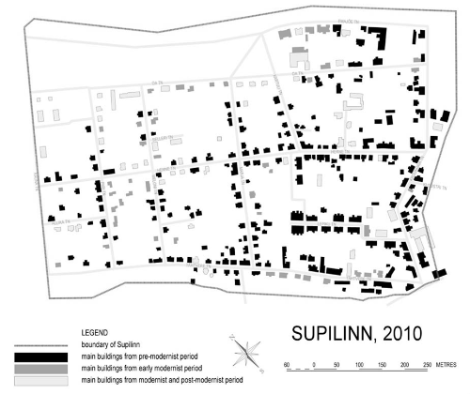

The area has preserved the original borders from the 17th century. As it was located outside the stone walls of the city, it experienced demolition and recovery several times in its history. Supilinn has been built entirely of wooden houses due to a government act that dates back to the 18th century. The state of the housing stock shows the permanent failure of the district’s renewal throughout its history.

The structure of Supilinn’s plots (plots of land, or lots) indicates the organic establishment of the district. While streets near the river follow the curve of the river bank, others are seemingly determined by previous planning. The plots stretch toward the centre of blocks and their shorter sides have buildings facing the street.

The district declined and became a slum during Soviet times. It became less popular as it lacked amenities and when new high-rise buildings were constructed, Supilinn did not meet the general residential expectations. It became an area for poorer populations who needed cheap housing with low maintenance costs, and thus it was inhabited by students, artists and workers.

Source: Hiob and Nutt, 2010 in Hiob et al., 2012, p.95

Socialist planning cherished ambitious plans for rebuilding Supilinn district in a grandiose style practiced at the time. Accordingly, the first plan of the area in the ‘50s suggested the complete demolition of the houses. This approach was mitigated with each passing decade. Subsequent plans aimed to preserve the basic structures of the district with renovation of the housing stock, the substitution of old wooden building materials with others, upgrading of the traffic system and public services, and the transformation of the residential function of the areas bordering the centre with public functions. However, none of these plans developed in the Socialist period were implemented and the district remained the same, increasingly deteriorated segment of the city. The lack of action due to insufficient funds contributed to the preservation of a unique district in its original form.

Threat of gentrification in the former workers’ district

In 1998, Supilinn was dominated by multi-flat houses with few facilities or no facilities at all. This was one of the lowest quality and oldest neighbourhoods in Tartu. The majority of the housing stock now consists of buildings constructed before the Second World War. 15% of houses were constructed during the Soviet era, and another 15% since 1991, when Estonia gained political autonomy. The buildings constitute a loose urban fabric. The residential buildings contain a small number of apartments, and the variety of the one- and two-story buildings bestows a unique atmosphere on the district.

The Supilinn district always had a heterogeneous population, and was able to conserve it. In the 1960s, the number of inhabitants was around 4000, but decreased to 1790 by 2011. The rate of juvenile population is increasing in the district, and it is higher than the general population of Tartu. It is also characterized by a higher percentage of tenants than other parts of the city.

The area could be an ‘ideal’ location for gentrification processes. It is located close to the historical centre of Tartu and in this sense it is a highly valuable area. It has a low-density structure, with old and run-down houses providing a cheap base for real estate investments.

The popularity of the former low-status neighbourhood increased sharply between 1998 and 2003 among local residents as well as among the whole population of Tartu. Real estate prices reflected the process: while prices in Tartu rose by 740%, the same figure reached 1870% in Supilinn. Real estate companies were quite active in the area in the periods of economic growth in 2005-2007, but local residents did not accept the new direction Supilinn was taking.

A comprehensive plan was adopted in 2001 by the city council. This plan allowed the renewal of the district and became a deliberate and official policy document that the gentrification of Supilinn could have been based on. The comprehensive plan proposed densification of the district (built-up proportion increased to 20-30%). An increase in the population, to 2700 inhabitants, was also planned. The plan allowed the creation of new plots, and construction of 60 more buildings in the neighbourhood (of which 20 were actually built). The chaotic plot structure and the streets were destined for renewal. The municipality was also interested in densification, in order to make the infrastructure network more efficient.

Most of these renovations and reconstructions (80%) were implemented with the intention to preserve the original facades and milieu of the district, and only a minority (20%) represented an irregular style of renovation. However these two different styles of renovation are not evenly distributed spatially. The south-west part of the district, which is the closest to the historic core of the city, kept the forms of the hundred-year old houses for the most part. The new modernist houses are spread across the district.

The way to sustainable planning

The Supilinn Association (Supilinna Selts) became the driving force for decreasing the pace of the gentrification process of Supilinn and applying a new, controlled form of regeneration. This locally based non-governmental organisation was founded in 2002. Its foundation had been anticipated by the first Supilinn Days street festival. Shortly after the success of the festival, local community members recognized that the explicit formation of the local identity through community building can be an effective way to preserve the uniqueness of the area.

The foundation of the Supilinn Association was supported by a social and legal context that enhanced the launch of several similar NGOs with an urban or environmental agenda. This process was initiated by public funding schemes introduced at the time (Open Estonia Foundation, National Foundation for Civil Society, Enterprise Estonia, etc.)

‘Community and identity formation’activities included diverse community programs such as a local folklore collection, a local newspaper (Supilinna Tirin) and the regular organization of the festival. The Supilinn Association also started important and effective advocacy work to transform the design of the urban development plan for the district. The organization conducted several surveys (first in 2004, then in 2011-12) in the neighbourhood to explore local preferences regarding the position of Supilinn and its regeneration. They could thus put pressure on the local government–and could increasingly cooperate with them–in order to re-regulate the development plans of Supilinn and avoid the population exchange and the removal of the former less wealthy population. The Association’s most recent survey, in 2010, highlighted the qualities that are valued by the ‘citizens of Supilinn’ and in other parts of the town: natural setting, proximity to the city centre, historic milieu, integrity and the sense of community.

An important aspect of the Supilinn Association is that citizens living outside the district also joined in the community’s activities and adhered to its objectives. One of the main supporters of the NGO was the Estonian president himself.

The Association started to work out a new plan for the district based on community activity and information gathered in the first round of the neighbourhood survey. In 2006 they were able to propose their own agenda regarding the renewal of Supilinn. In 2007 a new development programme based on the local needs of the district, was adopted by the local government of Tartu. The main principles of the new development programme stipulated that the structure of the plots, buildings and streets in Supilinn must be preserved. The existing streets must be renewed with historical materials and building schemes also have to historically suitable. The plan maximized the increase of the population to 2500 residents and touched on the unique and strong sense of community that arose in the neighbourhood and the heterogeneity and tolerance of its inhabitants.

Conclusion

In the example of Tartu the process of town planning was an instrument for urban renewal. As Hiob et al. (2012) state, the modified development programme due to the work of Supilinn Association “has not only limited the tide of demolition but encouraged responsible renovation” in the district. In this way the sustainable regeneration of Supilinn could be achieved. The means of renewal takes locals’ preferences into account and serves their interests, while also contributing to long-term preservation of the valuable historical heritage of the old wooden district. The intervention of the community in the renewal processes could not entirely stop the gentrification of Supilinn, but it has been slowed. Long term analysis of the district will show whether the negative effects of gentrification, such as displacement of the poor and a change in the identity of the district, can also be stopped.

Sources

Hiob, M., Nutt, N., Nurme, S., & De Luca, F. (2012). Risen from the dead: from slumming to gentrification. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 36. p.92-105

Jauhiainen, J. (2003) “Urban planning and land-use in post-socialist Estonia: The case of Tartu.”, in : Rydń L.(eds) Building and Re-building Sustainable Communities, Sustainable Urban Patterns around the Baltic Sea. Case Studies Vol. 2. Baltic university Press, pp.35-43.

Kährik, A. (2000) Housing privatisation in the transformation of the housing system-the case of Tartu, Estonia. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift, 54(1), 2-11.

Leppik, M. (2013) Ruumimuutused Supilinna piirkonnas. Uurimistöö aines Linnaplaneerimine ja keskkond.

Nutt, N., Hiob, M., & Nurme, S. (2012). The Story of “Ugly Duckling”. The Run-down Slum that Survived the Socialist System of Government Has Turned to Desirable Residential Area. In Proceedings of the 15th International Planning History Society Conference

Statistics Stonia (2014) Eesti statistika aastaraamat. 2014. Statistical Yearbook of Estonia.