Policies to reduce informal settlements: the influence of international organizations and the contradictions of public action

Phnom Penh, CAMBODGE

Valérie CLERC, 2014

Centre Sud - Situations Urbaines de Développement

This fact sheet presents the problem of land regularization in the Cambodian capital, where the declared will of the local and national authorities comes up against the many conflicts of interest that they have with local investors

Public action mixing antagonistic policies

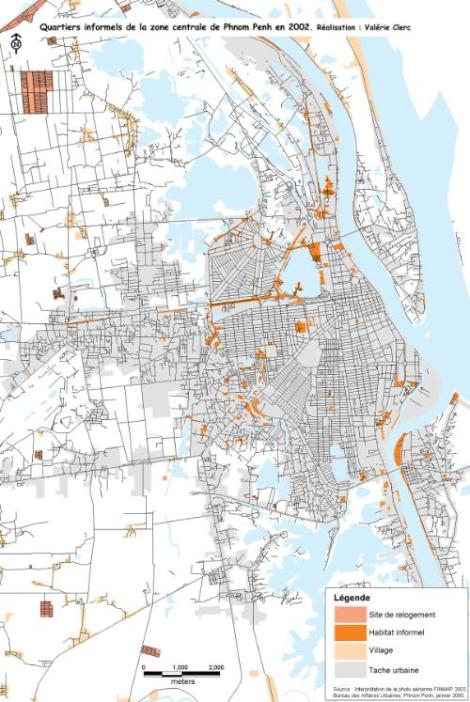

What about the recent history of policies for the rehabilitation and displacement of Phnom Penh’s informal settlements? The Land Law was passed in 2001. It provides for the provision of free land, under certain conditions, to families who cannot afford to buy land, in subdivisions built on the State’s private domain. The Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction (MATUC), supported by the World Bank and the Finnish and German cooperation agencies, has been implementing a land management and administration project since 2002 to establish land policies and register all land in Cambodia within 15 years. Provision is made for poor communities. In 2003, evictions and displacement of informal settlements were officially abandoned and a policy to regularize and rehabilitate the 500 or so identified settlements was announced by the Prime Minister. On the other hand, no national housing policy has emerged. The first rehabilitation projects were carried out without anyone coordinating them or officially counting them. And there has been almost no dissemination of information. The investors wishing to intervene on occupied land sometimes only discovered the Prime Minister’s promise during meetings with inhabitants’ associations.

Within this framework, 100 neighborhoods per year were rehabilitated at the beginning of the process, but their land regularization was slow to be put in place. This is done in conjunction with the land policy and, in fact, the rare beginnings of regularization are linked to the land registration process. Few inhabitants are therefore likely to obtain the land title announced by the Prime Minister. Land sharing projects are also hampered by the land issue. Rehabilitation, relocation and land sharing projects have therefore been pursued, without a formal framework, while the land policy was developed in parallel.

In fact, this announced policy of regularization and rehabilitation was neither formalized nor followed by all the expected effects, because another movement, in which members of the government - sometimes the same ones - also participated, went in the opposite direction and prevented its complete realization, making public action difficult to understand. While all municipal and governmental actors agreed with the Prime Minister’s speech on the need for action in favour of the poor, not all were convinced of the priority to be given to this action over others.

In principle, the announced policy was in line with the anti-poverty actions that the municipality had carried out in previous years. But in practice, on every piece of land that is to be rehabilitated, there are conflicts of interest. The land occupied by families, who sometimes have rights to it, is at the same time allocated to investors, who often have connections with authorities or members of the government. Arbitration, whether political or judicial}}, is often in favor of the investors, who want the land to be released. As a result, the possible regularizations underway are not successful, even when the neighborhood has already been rehabilitated. The government’s land policy plays an important role in this movement. The pressure on land has increased significantly. Investors are looking to quickly acquire any unallocated land, especially government land and buildings. The government gives up its public buildings to investors in exchange for land in the suburbs on which new facilities are being rebuilt. Informal settlements are sometimes established on part of these public lands and their inhabitants must then leave.

However, the contradictions in government action reflect the contradictions in the ideas promoted by international aid. For, while the United Nations, the World Bank and international networks and organizations encourage the implementation of a policy of regularization of informal settlements and housing for the poor, the World Bank’s assistance to the establishment of the cadastral policy stimulates the land market and leads to the bipolarization of land situations.

Sources

Valérie CLERC, « Du formel à l’informel dans la fabrique de la ville, Politiques foncières et marchés immobiliers à Phnom Penh » in Espaces et Sociétés n°143, December 2010, p. 63-79.

Valérie CLERC, « Les politiques de résorption de l’habitat informel à Phnom Penh. Influence des organisations internationales et contradictions de l’action publique » in Géocarrefour, vol. 80 3/2005.